On April 4th, a German indie studio called GrizzlyGames released Islanders, an atmospheric minimalist city builder. The game immediately got warm reception from critics and very positive reviews on Steam. Valve listed it among 20 top-selling games of April 2019.

Islanders is about making the best of very limited resources. So is the story of the real-world people behind the game.

Game World Observer talked to Friedemann Allmenröder, an artist and game designer who co-founded GrizzlyGames.

Friedemann Allmenröder, GrizzlyGames co-founder

Studying game design

GWO: Friedemann, the titles you worked on, ROM, Superflight, and Islanders, have all been done as part of your bachelor’s degree. Could you tell us about this degree and HTW Berlin?

Friedemann: First, I studied graphic design in Münster for two years. At that time, I interned at two German developers. One of them is the developer of Anno games. Those were actually the first people in the games industry I got to work for. I worked there for a half year. And then I worked at Deck 13. They made Lords of the Fallen and, most recently, The Surge. I interned as a concept artist in both cases.

Then I dropped out of the university in Münster and restarted studying in Berlin, at HTW.

I can absolutely recommend it if you want to get in game design. It’s a Bachelor of Arts in Game Design. HTW is a public university, so there are almost no student fees.

And they give so much freedom with your projects. Plus, it’s just a great environment to make games.

We were about 40 people per year. You know everybody you are studying with. We met as part of this bachelor program: Paul, Jonas, and me. [Paul Schnepf, Jonas Tyroller and Friedemann Allmenröder make up the current cast of GrizzlyGames—Ed.]

Game design students at HTW Berlin

Game design students at HTW Berlin

GWO: So every year you have to roll out a new game?

Friedemann: For the first year, you don’t. In the first year, you learn the basics. You have some smaller projects, but you don’t make a game yet.

Then, in the second year, they start you off with a 2D game. And there are very tight rules on what you can do and what you can’t do. The goal of that is to make sure that you don’t overdo it with the first one. That you don’t overscope while you are learning the basics. I think it’s a very clever approach to teaching people how to make games.

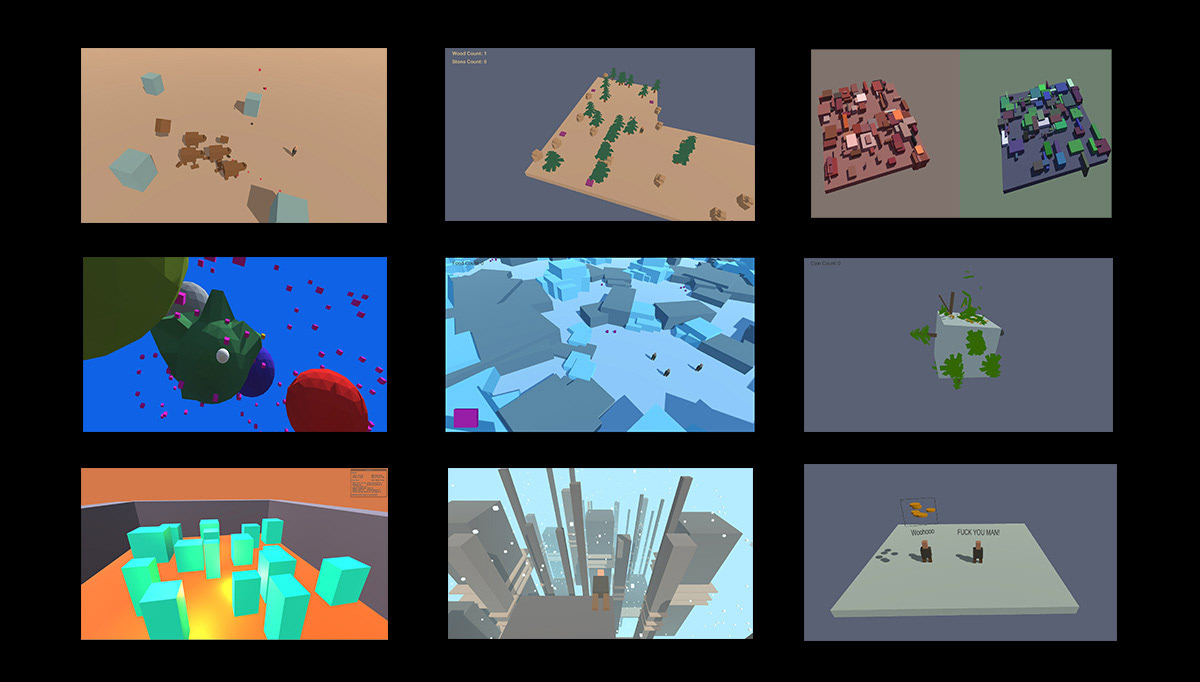

After that, every year you have some kind of project. The first thing we made was called ROM. It’s a very small experimental thing. But it was a good experience to just make something, finish it and publish it.

In the second year, we also made Superflight. Then there were some projects that we didn’t publish. And the next one was Islanders.

ROM

GWO: What was the role of your mentors from HTW Berlin?

Friedemann: As I said, they gave us huge freedom. Sure, we had some rules and limitations on what we can do. But those were good creative constraints.

Other than that, our mentors provided us with lots of feedback and coaching. Every two weeks, we met with them. We presented the current state of our game. And they pointed us towards mistakes that maybe we didn’t see yet.

But they always made it very clear that they were there to help us, give input on our project, but none of it was mandatory. It was up to us whether to implement their feedback or not.

GWO: They must have worked a lot in the games industry?

Friedemann: They don’t necessarily have games industry experience. They definitely have worked as designers. They have an art background.

If you ask me, it made sense that our coaches didn’t have a direct games industry background. I mean, all of the students are very games-focused. So our mentors added all kinds of interesting feedback from other areas. From more of an art perspective. Or design perspective.

Early concept art for Superflight

GWO: And where are you right now with your degree?

Friedemann: I am already finished. I finished my Bachelor’s thesis this march.

After Islanders, I headed directly into my Bachelor’s thesis. It’s an individual project. So, no team. I developed a 2D content creation tool for Unity and a game concept based on this tool. Then I wrote a paper about it. It’s not a scientific paper, it’s just lots of documentation.

Right now, I am figuring out whether I want to continue working on that game concept.

Setting up a studio

GWO: So how did GrizzlyGames come into the picture?

Friedemann: Currently, there are three of us at Grizzly Games. Jonas, Paul and me. Paul and me had finished Superflight with our friend Sha [Shahriar Shahrabi—Ed.] and the 3 of us founded the company as a way to release the game. Jonas joined later, after we developed Islanders together. All of us are pretty good friends, and spend quite a lot of time working on these projects together.

GWO: GrizzlyGames. That’s one strange name for a company.

Friedemann: One of the first prototypes for Superflight included exploding grizzlies. You were a hunter, and you were shooting a bow and arrow at grizzly bears who were attacking you, and then they exploded.

We immediately dropped that idea because we decided to make a game that didn’t include violence. But for a limited time, we had grizzlies, we had already programmed them. We put the exploding grizzlies into Superflight, and they were targets that you could hit when flying through the levels.

Then, at some point we had to sit down and come up with a team name for the company. And somebody just brought up GrizzlyGames. We thought it sounded fun and went with it.

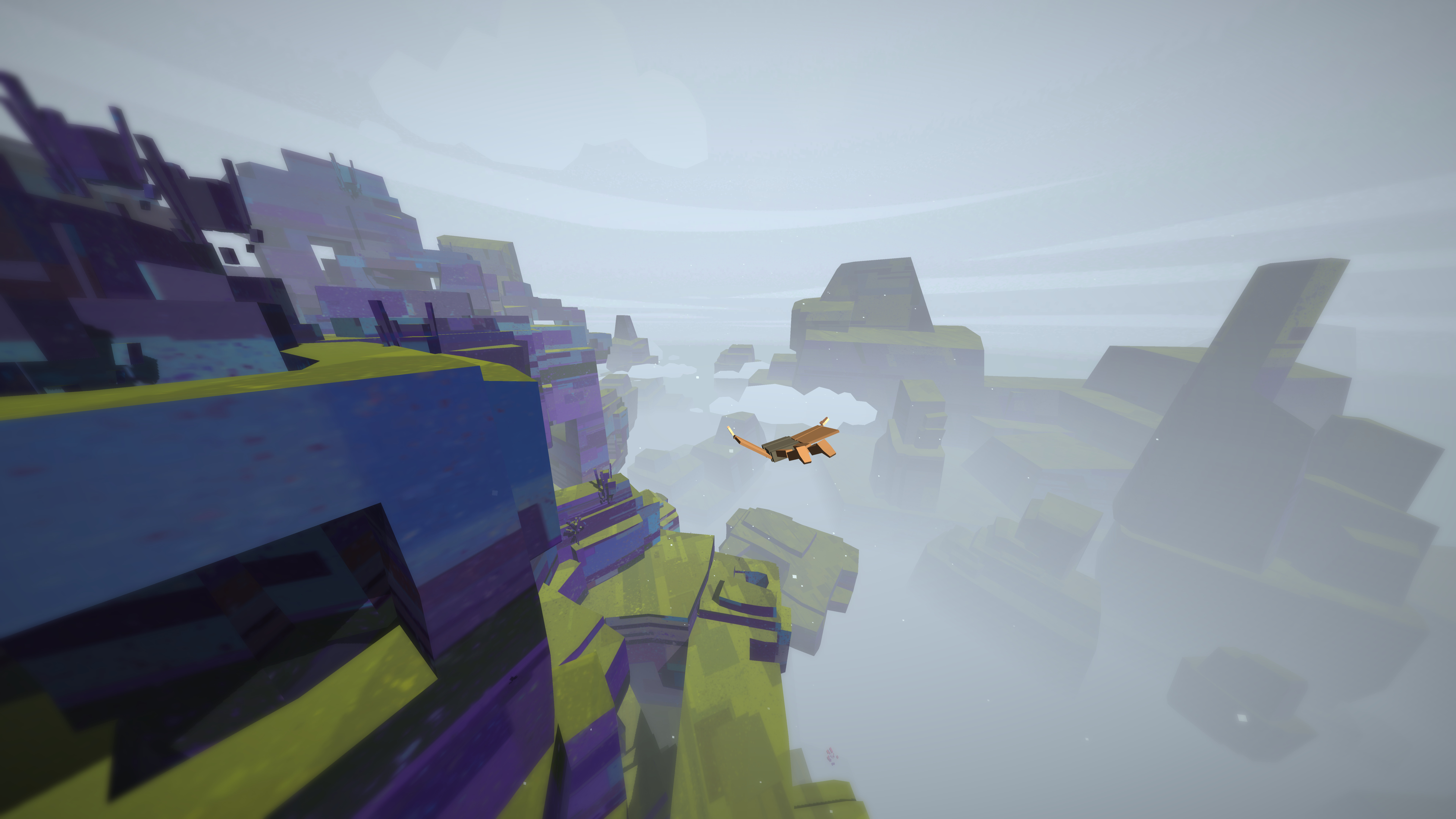

Superflight

GWO: The three of you are friends. You study together, you work together. That’s a lot of the same people all of the time. How do you not feel like you are stuck on a submarine with each other?

Friedemann: Because we spend so much time working together, we don’t spend tons of time outside of game development. We already hang out for seven to eight hours each day. We sometimes get a beer on the weekend or go bouldering together, but normally after work we spend time with other people.

GWO: Anyway, the company stays even after you graduate?

Friedemann: It’s going to take us some time to reorganize. I have already graduated. Paul has just finished an internship, and he’s going to graduate next year. Jonas is working on his new game and YouTube channel. We are going to be working on some separate stuff for a bit now. And then come back together and start working on the next project, after we finish the Islanders post-launch support.

Making games

GWO: Let’s talk about your games. What’s your role on the team?

Friedemann: The fact that we are such a small team means we all have to wear all hats. All three of us would be able to make games on our own if we had to. Anyway, my area of expertise is sound and visuals.

Islanders

GWO: It took 3 people and only 3 months to create Superflight. Islanders was also created by 3 people in a very short 4 months. How do you explain this kind of efficiency? Is it about the minimalism of your projects? Or maybe the minimalism is the result of your team being so small?

Friedemann: The simplicity of our projects might have been born out of necessity, but we really embraced it and turned it into one of the core pillars of our philosophy.

Of course, it wasn’t only a creative decision. We wouldn’t have been able to make bigger games. But in both our products so far, we specifically aimed for this super minimalist approach in design.

That’s the main reason we were able to maintain these super short production cycles. Every time we made a decision, we asked ourselves: Can we make it simpler? Can the game still be fun if we cut this feature? Can we combine them to a simpler thing?

Superflight

With Islanders, we initially had a day cycle in the game. You had to make enough points to earn access to the next day. Then we realized we could just cut the day cycle and simply give you more buildings for more points and thereby simplify the game even further.

It’s a fun way to make games for us. And the games created this way are really accessible for a broad audience. So we are going to stick to this approach.

GWO: Let’s talk about procedural generation. Again, is it something you have to rely on due to the lack of resources, or is it more of a choice?

Friedemann: It’s the same as with the simplicity. It started with Superflight. We wanted to quickly test levels. And in order to just generate a random number of levels, we put together a script that assembled things from blocks.

Then we realized that the cool thing about procedural generation is that you can keep playing your own game even though you’ve already spent so much time on it. The three of us really value it in the development process. That you can still have fun with your own game.

In a game where all the content is handcrafted, where you have made everything, that goes down really quick. Take ROM, for example, the experimental game we made at the beginning. I have just seen everything that’s in there because we made it by hand.

So I really appreciate the fun that you can still have with a procedurally generated system. Like with Superflight. I still sometimes start it up and just fly for five minutes or so.

By adding procedural generation to our titles, we can ensure that even at the end of the development cycle, we can still ask ourselves: is it fun for us or not.

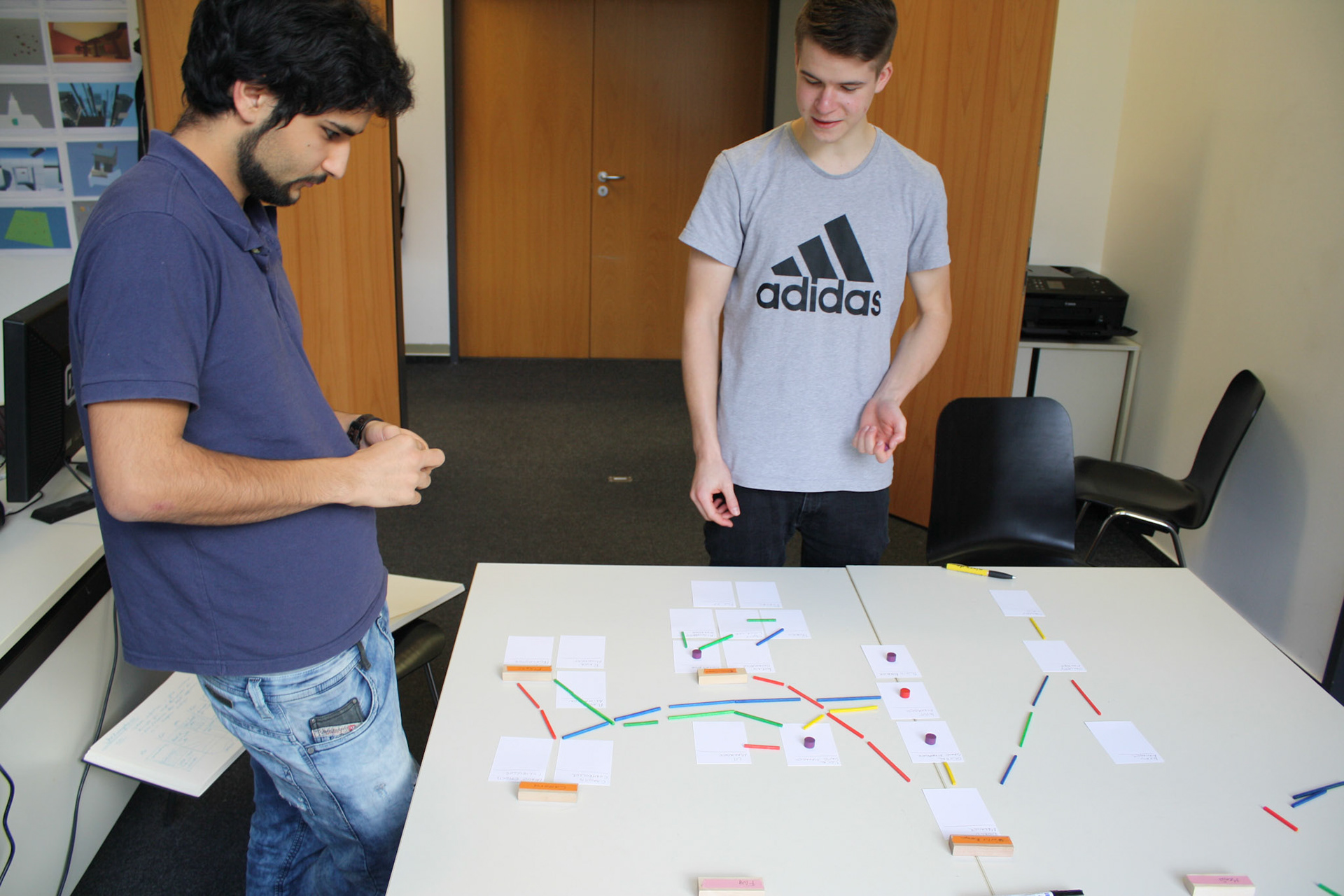

GWO: On your blog, you mention analog prototyping as part of your process. Could tell us how this works exactly?

Friedemann: That’s something our professors at the university really pushed us towards. We have tons of materials. Wooden building blocks. Lego blocks. Paper and stuff.

When we start thinking or talking about prototypes, we usually just bring those materials to the table and use them to visualize things or to quickly create a little setup for something. To make a level mockup. Or if you want to just convey an idea to the others, how it could look. We use these materials to quickly iterate and show to others what exactly we are talking about.

Prototyping for Superflight

The big difference between this and digital is that it’s super easy to collaborate. It’s really quick because everybody can just move things around on the table. It removes the possibility of misunderstanding each other. Sometimes you talk about an idea, and everybody agrees that it sounds awesome, and then you start making it, and you realize you have three completely different visions between you. Quickly visualizing things in a physical manner really helps to eliminate these misunderstandings.

GWO: And somehow, the physicality of it translates into your games.

Friedemann: True. The blockiness of our games. That definitely comes from prototyping.

GWO: Is there any evolution from Superflight to Islanders?

Friedemann: There’s just a general trend to push everything further. We tried to add a little more detail and fidelity to the visuals. We added music this time. Which was scary. All of us are really amateurs when it comes to music production. We have all kinds of features that we didn’t have before.

So yes, there is definitely an evolution from Superflight to Islanders. The scale is bigger. We tried to offer a little bit more depth and replay value for the players.

At the same time, we tried to remain true to what Superflight was, to our core brand of making these really small fun experiences that you can play in a very healthy session length. You don’t have to play our games for 40 hours to get value from them.

Preserve simplicity, especially accessibility. That’s the biggest point for us.

It’s going to be interesting to see whether this trend continues. Is our next game going to be more complex than Islanders? I don’t know. Maybe we will take a step back and try to make it even simpler.

Anyway, the general philosophy is not going to change. It makes it easy to stay healthy for us. It creates healthy and fair products for our customers. And we don’t have aspirations to expand the company. If the games make enough money to finance the next development cycle, we are going to keep it at this.

Islanders

GWO: How do you come up with ideas for your games?

Friedemann: We have a set process for developing game ideas.

First, we spend one week just researching random things. We go to the zoo. We watch documentaries. We read stuff in the library. We literally sit down in the library for a day, pick books from the shelves and read them. Paul gave us a really interesting presentation about bees in Germany, when we were in a prototyping phase for Islanders. So, we just soak up information to have things to build from.

Then, starting from that, we spend another week building tons of small prototypes. And you can’t spend more than one day on each prototype. They are just meant to flesh out your ideas really quickly and test if there’s something fun there.

After that, we take all of those prototypes we’ve made and pick the ones that we think are most interesting. And then we spend another week refining and iterating on these initial prototypes and see if we can come up with a more complete game systems from those.

With Islanders, all three of us played builder games as children. So we decided to create something that captures the aesthetics of these games. Anno, The Settlers, Sim City.

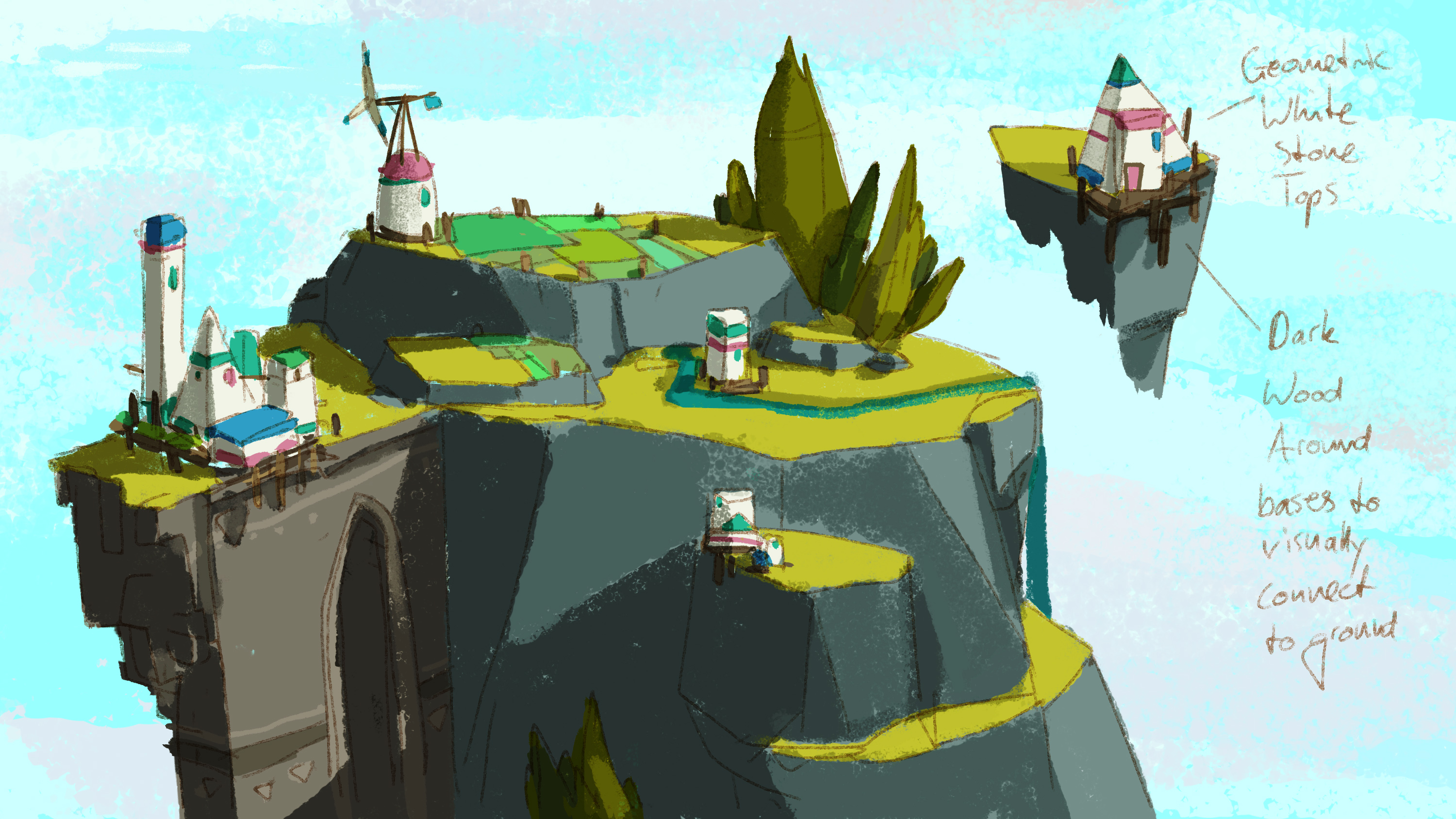

Concept art for Islanders

GWO: What is the most difficult thing for you on any of your game projects?

Friedemann: Definitely finishing the game. In such a short timeframe and with our resources. Right now we can hire some freelancers. But in the beginning, it was just the three of us. And we had to do everything from sound to producing the trailers, to setting up everything on Steam. That’s super hard. Everybody underestimates it, including us.

From the point where you think you’ve got the finished game to actually pressing the release button…There’s so much in between those two points that we underestimated. For the projects we’ve made so far, that’s been the toughest part. You really have to cut features that you love. And you have to make really tough decisions in order to reach this release point.

Marketing games

GWO: And do you market your games yourselves? How do you do it?

Friedemann: Yes. It’s the same minimalist approach as with our game design. We try to make very few but focused marketing efforts. Two trailers for both of our products. We try to be very honest and upfront about what our games are. Obviously, we want as many people as possible to see the game. But our goal is to make sure that our potential customers are actually informed on what the game is. So if you decide buy the game, there should be a really good chance that you will enjoy it. We don’t want to create artificial hype and try to sell it to as many people as possible regardless of whether they are interested or not.

So far, that’s worked pretty well. And I think people have appreciated that. So we are going to stick to it.

GWO: What about showcasing your products at game conferences? You participated in Quo Vadis 2017, right?

Friedemann: Quo Vadis was just a little test for us. It was the first game conference that we ever went to. We just tried what it’s like to be at a fair. I’m personally a bit skeptical about the marketing value of game conferences. It’s super cool to meet other developers and players, but also it’s very costly. You have to get all your gear together, ship it to some place, build it there, and spend a week with the team at a conference. So I think from a marketing perspective we are not really aimed at conferences that much. It requires a lot of work and preparation, and we have to consider it carefully given how small we are.

Team nominated for the “Best of Quo Vadis” Award

GWO: So how do you keep in touch with the community?

Friedemann: The fact we have been very open and honest about our games has led to our community being really positive, and honest, and appreciative of what we do. So far, it’s been really fun to have just very direct communication with players.

We keep in touch through Steam discussions. And if people want to write us emails, we make sure to read every email and try to get back to them.

Again, the minimalist approach. That’s why we don’t have an official Discord channel or an official subreddit for our games. It would just take up too much time to maintain all of these channels. So we have very few. But in those communication channels we make sure to interact with people, to read everything.

GWO: As a very young studio, what is it that you still need to learn?

Friedemann: The hardest challenge is to be sustainable in the long run. We still have to prove that we can keep up this development cycle, making games that financially sustain the studio.

I am really optimistic. We have a bunch of game ideas that we can pursue. There’s an audience for our games, we’ve shown that. We work very well as a team.

The question is the entire business side, we are still new to that. We still have to figure out how much money we actually need now that we can’t work at the university anymore. We have to rent our own studio space, things like that. So it’s a challenge that we have to face in the next couple of months.

GWO: Islanders only costs 4,99€ on Steam. Is it enough to last you until the next game comes out?

Friedemann: We had to calculate the price ourselves. We feel like it’s a fair price for both our titles. Compare them to other games, how big the teams were, and how long it took them to make those games. Islanders was made by three people in half a year. I’d say, five bucks is a very fair deal. Both to us and the players. If the next game ends up a bit bigger, maybe we are going to go for seven bucks. If it’s smaller, we are going to go lower than five bucks. That’s what we are trying to hit with our pricing. A place where both our players and we feel like everybody’s getting their money’s worth.

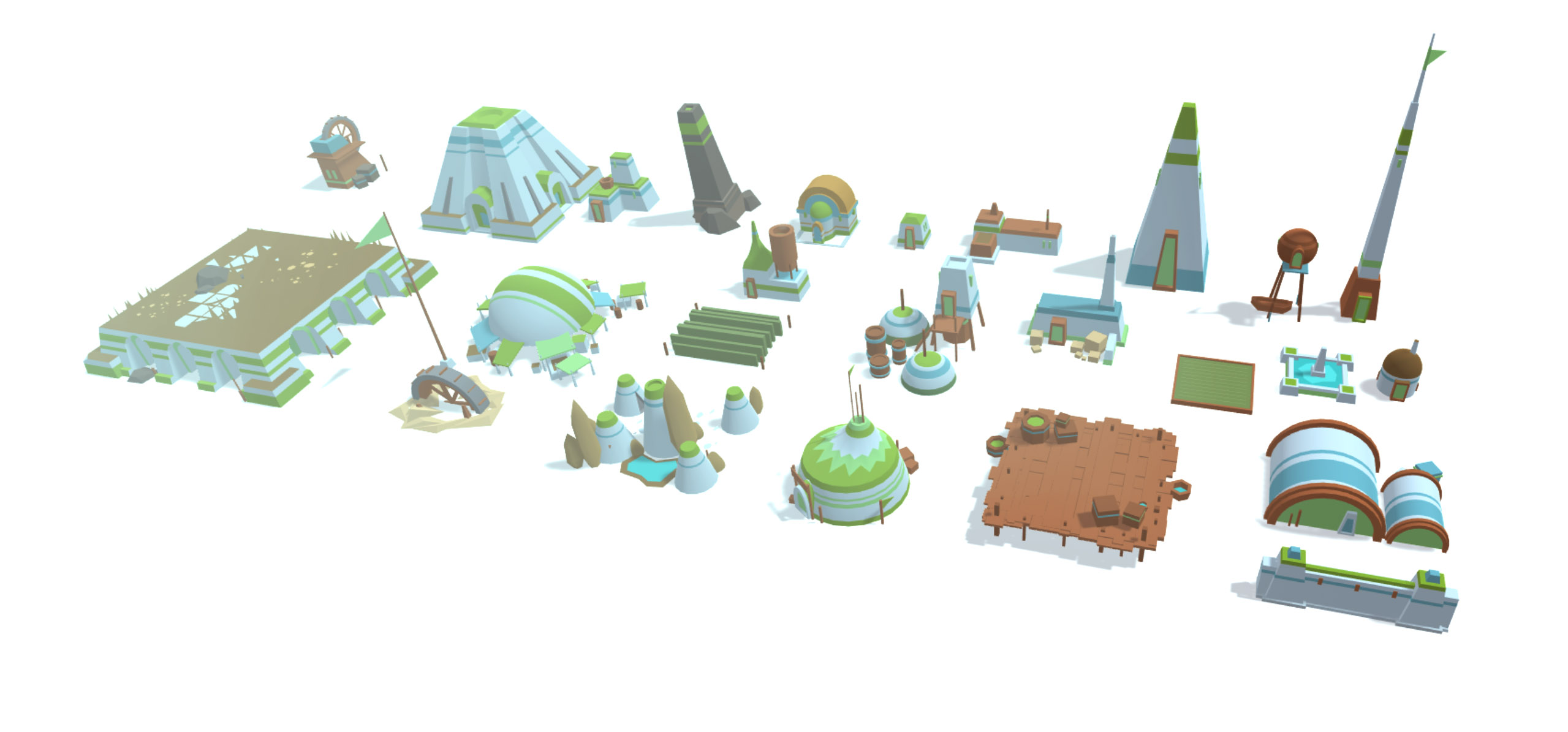

Ingame models for Islanders

GWO: So what are you up to right now? Are you planning to go on supporting Islanders or move to another project?

Friedemann: Right now we are mostly focusing on post launch support for Islanders. There are a few rare bugs still left in the game we are trying to get rid of. We have already published the first content update where we added some additional features, some new building and island types. Right now we are working towards the next content update. It’s too early to say when it will launch because we are such a small team and it can always alter a little bit depending on how much time it takes us to implement things.

GWO: How long are you going to support the game?

Friedemann: Maybe for two months or so. There’s one major and a few minor features that we would like to see in the game. But after that, we are going to start moving to the next project.

With Superflight we did the same. We added some small things, and then we wrapped it up, made sure the game was in a good place and moved on.

For everybody, including us and the players, it’s a really good deal. For us, it means we don’t have to keep working on the same thing forever, which can get tedious at some point. So we are happy to move on to new challenges, come up with new ideas. And for the players it means they’re going to see a new game from us sooner rather than later.

GWO: Looking forward to it! Thank you for the interview!