In October, another installment came out in the Game Design Deep Dive book series by Josh Bycer. Josh is a game design critic and lecturer. Through his website Game-Wisdom, he has interviewed hundreds of video games professionals about what it means to create video games. Josh’s latest book is focused on the horror genre. A little late for Halloween, we still decided to catch up and discuss what makes a good horror game.

Josh Bycer

Josh Bycer

author of “Game Design Deep Dive: Horror”

founder of game-wisdom.com

Oleg Nesterenko, managing editor at GWO: Hi, Josh. Why don’t you start by telling us a little bit about yourself? How did you become a game design critic in the first place?

I’ve been interested in video games for a very long time. At first, I just experimented with a little blog on video games. Then, in 2012, I launched a website covering the industry that I called Game-Wisdom. From there, I started reaching out to developers, and by now, I think I’ve done over 600 interviews on game design. I’ve talked with developers, members of the press, students, and just video games enthusiasts. It was audio casts at first, but in 2016, I started my YouTube channel.

Some of my higher profile guests include Jon Shafer [US game designer who worked as lead designer on Civilization V], Ernest Adams [US game designer, writer, and lecturer], Chris Park [indie developer, founder of Arcen Games], and then, most recently, Star Control creators Fred Ford and Paul Reiche.

Being able to speak to people who have been in the industry for so long helped me develop my own approach to studying game design. So, around 2018, I started working on my first book, 20 Essential Games to Study. It was originally just going to be a very small ebook, self-published, nothing fancy. But CRC Press got in touch with me and asked me if I had any ideas for books. And I was already writing something. So that’s how 20 Essential Games came to be. Afterwards, I decided to take that further with the Game Design Deep Dive series. That’s just me throwing all my thoughts and research methodologies on various game designs on a genre-by-genre basis. The first book in the series was on platformers, the second one was on roguelikes. I’ve just finished Game Design Deep Dive: Horror, and I’m already working on my next book on free-to-play, which will be coming out sometime in 2022.

Game Design Deep Dive: Horror promo art

In your latest book, you look at how horror has evolved in video games. What was your approach to mapping out the history of the genre?

I divide the history of horror video games into four periods.

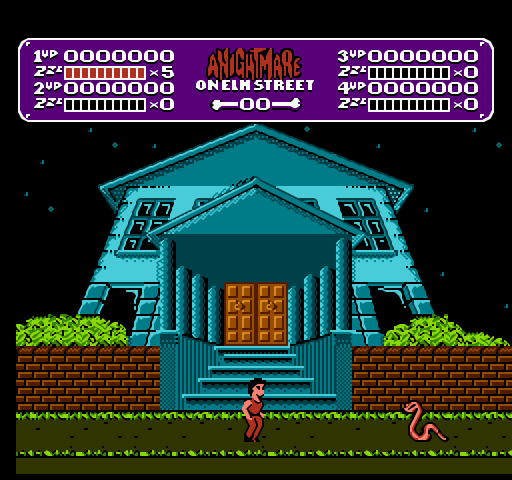

- The first period encompasses so-called “pre-survival horror” games released in the late 80s and early 90s. They involved horror iconography or elements, but weren’t necessarily what we would consider actual horror experiences. These include old school LJN games, like Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Gremlins and many other licensed games.

- Next follows the survival horror period. This would be the mid-90s, early 2000s. Alone in the Dark, Resident Evil, Silent Hill. These titles would become the foundation and the benchmark for what a lot of people consider to be the survival horror genre, which culminated in the rise of a slower-paced horror design.

- Then, after mid-2000s and especially in early 2010s, we saw the decline of survival horror, while a more action-oriented horror emerged, which is, of course, Dead Space, Resident Evil 5 and 6, and their many imitators and competitors like Alan Wake and Evil Within. That’s the third period.

- By about 2014, this action-heavy “mainstream horror” started showing signs of decline. And that’s when we got into the fourth period dominated by indie horror. Now we’re talking about Five Nights at Freddy’s, Outlast, Phasmophobia, Amnesia. All these independent developers pushed back against AAA horror games. In most indie horror titles, there’s not a lot of fighting, they are slower-paced, very jump scare-focused.

The book ends with my thoughts on where horror is right now and where it can go from here.

A Nightmare On Elm Street, 1989

And how do you explain these shifts in the paradigm, these transitions between various horror subgenres?

When we talk about the rise of survival horror, many people give credit to games like Sweet Home and Alone in the Dark as the titles that shaped the genre. But one of the big things I talk about in my book is the influence of Resident Evil and Shinji Mikami. Capcom set the tone with RE 1, 2, and 3. And then everyone tried to follow them, thus constituting what I call the “survival horror” period.

Then, Resident Evil 4 came out in 2005. And, love it or hate it, it was the signal for action horror. One of Capcom developers said in an interview that survival horror wasn’t really viable anymore. The publisher decided to make Resident Evil more action-heavy because they wanted to pull in the same numbers as Call of Duty and Battlefield.

After RE 4, everyone decided that old horror was dead. And we saw this push to try and emulate the RE 4 formula with Dead Space and Alan Wake. Even after Shinji Mikami left Capcom and wasn’t there for 5 and 6, he tried to do it again with Evil Within.

Resident Evil 4, 2005

In 2010, we also started to see greater focus on multiplayer, this was the era of Team Fortress and League of Legends. We saw the trend towards the GAAS model. Not that developers thought that single-player games were dying, but there was this general assumption that there was more money in multiplayer. And in order to do multiplayer, you have to go huge. This is when Dead Space 3 shifted towards multiplayer, which a lot of people didn’t like.

The problem with AAA companies making action-heavy games to play with your friends is that it is in direct conflict with what you want in good horror. Horror is not meant to be about drinking with your friends and having a good time, it’s meant to give you a minor heart attack. So horror can never be a mass market genre. There will always be more people who want to play PUBG, Call of Duty or Fortnite rather than play a game alone in a dark room scared of things attacking them from behind. The very best horror game is not going to bring in anywhere near the same amount of cash.

Fortunately, the rise of the indie space allowed developers to do a lot with very little. They didn’t have to compete with Fortnite in terms of earning money. So the indie community pushed back hard on what became mainstream horror. This is when Frictional Games got really big with Amnesia. From there, we saw developers going more towards a storytelling-focused and environment-based horror with Gone Home and Outlast, and, of course, Five Nights at Freddy’s. Developers basically said, “We don’t want you, the player, to be in control. We don’t want to give you all the guns and have all the licensed music in the world. We want to sit you down and then go ‘boo’!”

Five Nights at Freddy’s, 2014

And this was great for the genre because true horror is about psychology. If you understand what are the right levers to pull to make things scary, you can make an eight-bit pixel art game absolutely terrifying, probably way more so than a game that uses the latest Unreal Engine and HD graphics.

Let’s talk about these levers, shall we? What devices are there that devs can use to make their game scary?

The psychology of horror is a major point in the book. In fact, I spend more time discussing psychology than talking about actual mechanics. Horror is more of a thematic genre. It’s something that you can fit any mechanics and systems into. There are horror cooking games, horror golf games, horror visual novels, dating, racing games. The list goes on. It is psychology that makes horror what it is.

As H.P. Lovecraft famously said, “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” Horror games are meant to be played blind. You can really experience each game one time only. You can replay any multiplayer shooter, any esports game or a deck builder, but with horror, you’re only going to get scared by that dog jumping out of the window in Resident Evil one time.

The first time you meet Pyramid Head in Silent Hill is probably going to scare you, or the first time one of the puppets gets you in Five Nights.

Your challenge as a horror game designer is, then, how long you can keep the player in the dark, how long you can keep them confused as to what is happening. The second you lift the curtain, horror is gone.

Silent Hill 2, 2001

This is why horror games cannot be very long. A 50 to 100-hour game would never work with horror. You will never be able to sustain that experience.

To be fair, I don’t think there’s any video game out there that has maintained the right horror atmosphere for all the way through its entire experience, even Resident Evil and Silent Hill. Eventually, you get to that point where you’ve seen all the jump scares, you have your best weapons, and from that point on, it’s “bring it on.”

You should also understand the pacing of good horror. It’s not just about throwing everything at the player all at the same time. Nor can you just let them wander around for seven hours and have a creepy noise play in the background every now and then.

And speaking of creepy piano tunes and stuff like that, I really push back against jump scare-focused horror, because if it’s just a jump scare and then nothing at all happens, horror is gone. Jump scares need to be tied to something, to a consequence, they need a follow-up, so to speak.

Last but not least, you should understand the difference between using horror themes and actually designing horror. DOOM has horror themes and imagery, such as demons from hell, but it’s not a horror, it’s a power fantasy. A lot of action horror really leans into this power fantasy idea. Necromorphs in Dead Space are big and scary, but only until you blast their limbs off with your railgun. When DOOM Eternal tells you to “rip and tear until it is done,” you’re not supposed to be scared. The enemies are supposed to be scared of you. Or when Chris Redfield does wrestling moves on zombies, we’re done with horror.

In true horror, they can give you all the guns and knives in the world, and you’ll be terrified to use them. True horror is not about running into every encounter with guns blazing. It’s about never being sure if you can survive.

I recently played Cry of Fear for the first time, which was originally developed as a Half-Life mod. It’s a game that gives you shotguns and assault rifles, but you are still fumbling around in the dark while crazy monstrous junkies are trying to beat you down or something is chasing you with a chainsaw. It never lets you feel invincible.

Cry of Fear, 2013

These are excellent points. Unfortunately, the fact that you can only be scared of something once reduces the replayability of horror games. Which, again, makes them less economically attractive than other genres. In your book, though, you do mention something called “procedurally generated horror,” which supposedly can solve the issue of experiencing things for just one time. Do we have viable examples of that in horror games, or is it just a concept for now?

Procedural generation or procgen is something I talked about heavily in my roguelike book because it’s obviously a major facet of that design.

The goal of procedural generation for horror is that the player cannot predict what is going to happen next, be it where enemies show up, where jump scares or important things are. We’ve seen this done on a small scale in, for example, Slenderman games, where they challenge you to get seven things in the environment, but each time, those seven things would be in completely different places.

But that’s on the low end because the scares themselves are still very much the same. You know that the lights will flicker eventually, that there’s an enemy nearby who will behave a certain way. But what if the entire situation could be different each time? What if you could have a killer that is built on several different variables or several different strategies?

Imagine that this killer is created much the same way a level in The Binding of Isaac is stitched together. Or think of something like a Hades run. Then the player doesn’t know what to expect.

There is this upcoming game Shadows of Doubt, in which NPCs are procedurally designed based on the HEXACO personality model. It allows you to create characters using variables like extraversion, openness to experience and emotionality. But we are yet to see how that works in the final game.

There are very few examples of this, because it is such a hard kind of design to do. I cite two examples in my book. One is Golden Light by developer Mr. Pink. This is a very grungy, very PlayStation 1 era-looking game where every floor is procedurally generated. You have an objective, but you don’t know where that objective is. You don’t know when enemies are going to come at you. And almost every enemy in that game is a mimic. So the game throws random objects in the environment, and it works because one of those random objects could be an enemy that will pop up and try to attack you when you walk by it.

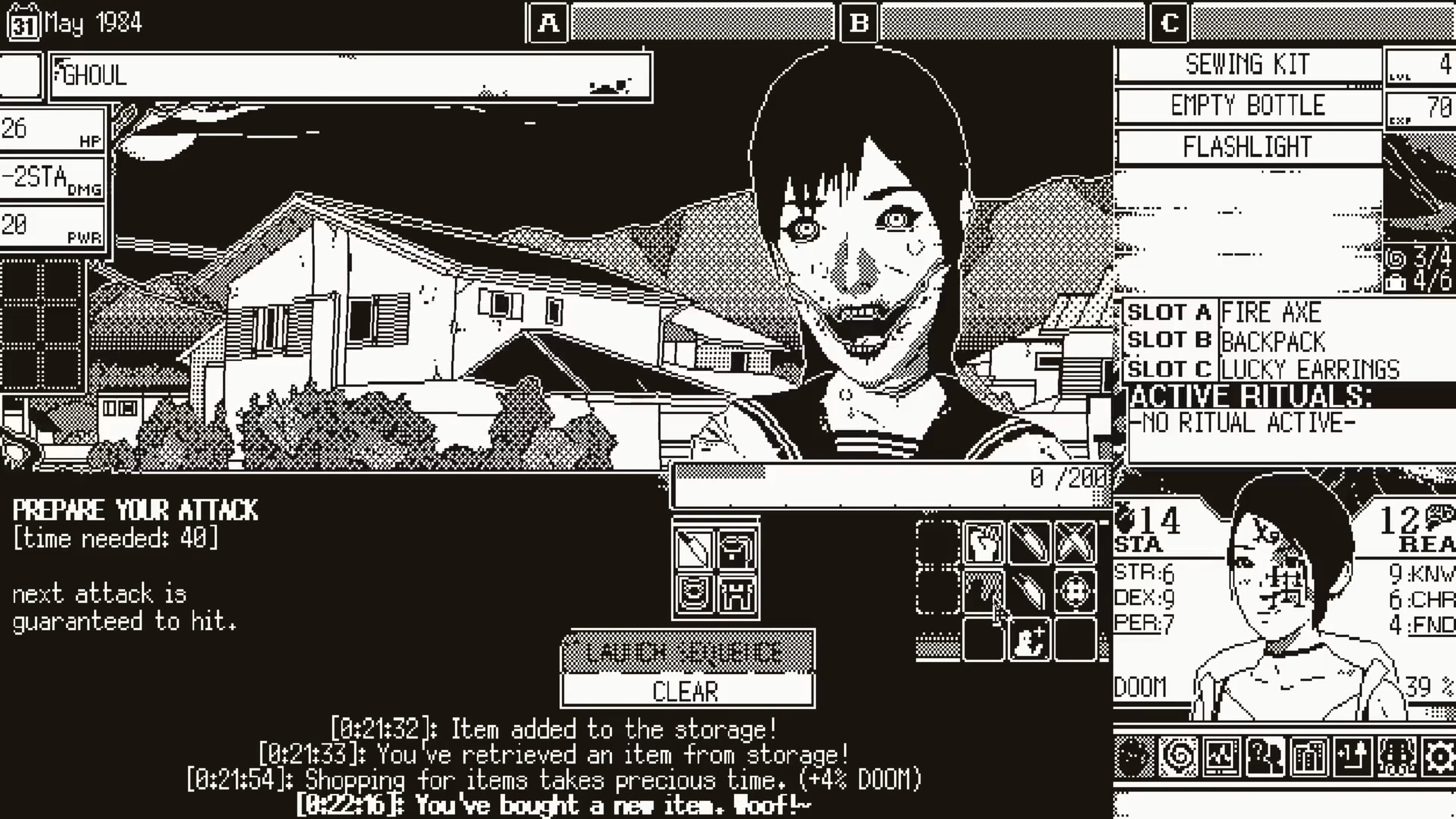

And the other example that I really like is World of Horror because the game chooses different cases for you to go after. These cases frame what story the game tells, and all the events and points of interest are randomly chosen from its pool of 200 or 300 items.

World of Horror, 2019

Now the problem, other than it being hard to pull off, is that throwing in procedural generation means you’re losing control of the experience. A well-defined one-hour horror game could be fantastic because every aspect of it is handmade. With procedural generation, that’s no longer the case.

But I do think it is very viable. We’ve seen procedural elements work to great effect in r-oguelikes, I think it’s possible to scale that and apply to other genres.

Perhaps, advances in the AI space can help devs design increasingly compelling procedurally generated experiences. What else do you think we can expect from horror games moving forward?

What is the future of horror? It’s the very last thing I talk about in the book. And it’s a tough question! Honestly, I’ve given up trying to predict major trends in the game industry because it moves so fast. All it takes is one game that comes out and upends everything, be it Fortnite, League of Legends, Celeste, Disco Elysium.

I think we are on the uptick. AAA developers have seen the success of Resident Evil 7 and 8, not to mention the remakes of RE 2 and 3. Konami recently released the Castlevania collection. There is value and money in these IPs. But we are yet to see if more AAA developers will follow suit.

I think it’s starting to happen! EA Motive is supposedly taking notes from Capcom’s remakes with their recreation of Dead Space.

Correct! And that poses a new challenge for independent developers. Now that the mainstream devs have been reacquainted with horror, it’s up to the indie space to come up with new ideas that will disrupt the genre.

Over the last two years, indies have been experimenting with the PS 1 aesthetic. There is the Haunted PS1 Demodisk series. We’re seeing more of the Dread X developers go for this kind of PlayStation 1 look and feel. But that’s not iterating, of course. That’s not evolving. We can trace lines from Alone in the Dark to Resident Evil, to Resident Evil 4, to Amnesia and Outlasts, but where is that next line going?

And that is where I don’t really have an answer. Horror is a very risky genre to do. At the AAA level, if you go to a publisher and pitch a three-hour horror game, while someone else pitches a multiplayer shooter, they will probably give money to them. Because that’s where there’s more value for them.

However, a few years ago when I was writing my book on roguelikes, I was wondering if somebody would do AAA roguelike? And you know what? Since then, we have seen that with Arkane. They did Prey: Mooncrash. They did DEATHLOOP. We’ve also seen that with Hoursemarque. Their roguelike Returnal blew up on the PS5! So my question is, are we going to see a AAA equivalent of Five Nights at Freddy’s, Outlasts or even Puppet Combo games (considering the latter’s style, it’s pretty self-contradictory, I know!)?

Murder House, 2020 (Developed by Puppet Combo)

In any case, if you want to see the genre grow and not just sustain it on life support, there need to be fresh ideas. The procedural option is one way to go, there may be others, but somebody should really try and push that.