Annapurna. Versus Evil. Raw Fury. Is working with these publishers a dream come true for indie devs? Alex Goodwin, the solo creator of much anticipated title Selfloss, has been there, done that. In an interview with Game World Observer, he shares his experience and warns fellow creators to curb their enthusiasm.

Alex Goodwin, indie game developer

Oleg Nesterenko, managing editor at GWO: Alex, a few words about yourself and Selfloss?

I’ve been making games since around 2016. Back then, my student project won the Grand Prix at an awards show for indie games. Since then, I have released two full-fledged commercial titles on Steam, all without a publisher [Algotica Iterations (2017) and Mechanism (2018) — Ed.]. I made them on my own, no external developers or outsourced marketing. At that time, like most newbie indies, I thought that since I was making a game, I knew best how to market it. Like why would I want to waste a percentage of my revenue on publishing? Since then, I have grown up as a developer.

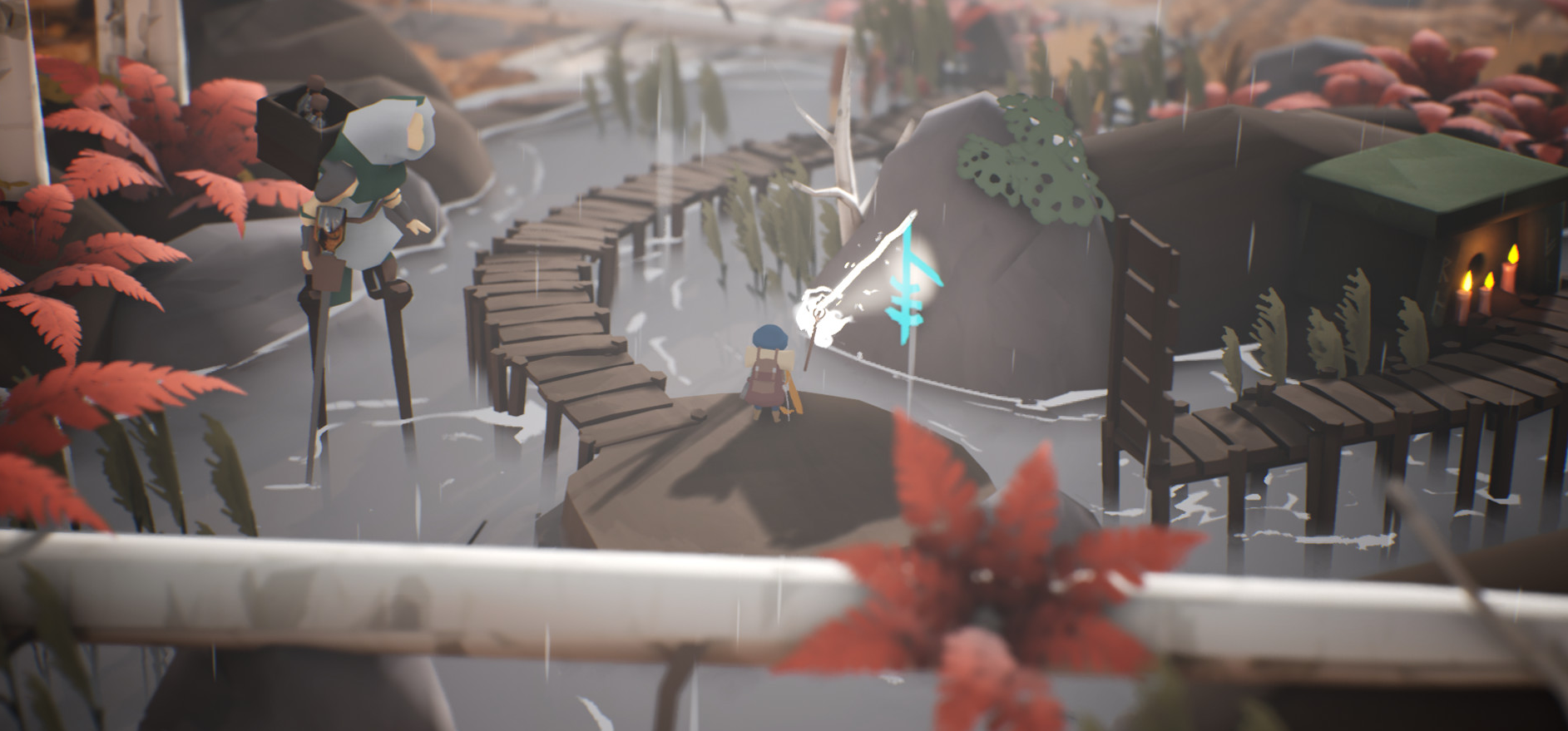

Now I’m working on my third game, Selfloss. I’m building it on Unreal, unlike the two previous projects that I made with Unity. This time, I knew from the very beginning that I didn’t just want to focus on the production part. I wanted to learn everything that’s happening around development, including marketing and publishing. And it’s not that I want to see if I can make more money with a publisher. I just want to get this experience. I think at some point you need to work with a publisher to understand how the industry functions.

How long have you been working on Selfloss?

I started making Selfloss at the end of 2018, but at the time, I was pretty busy at graduate school. So I really committed to the development in the summer of 2020. But as early as 2018, I knew that I would set up my processes so as to attract not just players, but publishers, too. For the sake of getting connections, if nothing else.

And? Did you get the attention of publishers right away?

In 2019, Selfloss was featured in Indie Cup, Eastern Europe’s largest indie games contest. It was then that publishers started reaching out. Or maybe a bit earlier, when Selfloss won Best Indie at another show. At first, it was four or five small publishers, like Crytivo. But during the three years since the beginning of development, I talked with around 40 or 50 different publishers in total. Of these 50, I myself have only approached two, Annapurna and Versus Evil. The rest of the publishers initiated the communication themselves.

And you knew from the get-go what you wanted from publishers?

Well… I think the first one to contact me was Crytivo. Actually, they left a very good impression. Sometimes I feel bad about failing to keep the conversation going on my end. I thought I was ready to communicate with publishers, I just didn’t expect them to start emailing me three months into development. At the time, I wasn’t quite sure what kind of game Selfloss was shaping up to be. But there they were, proposing revenue share numbers, discussing platforms, while I had no idea when I would even finish the game. And so I kept putting off these conversations, and at some point they stopped calling. I don’t blame them.

Awkward!

You have no idea. But maybe this is something not a lot of publishers appreciate enough. To them, it might look like developers are sabotaging the talks on purpose. But they aren’t! It’s just that publishing companies are often made up of business development folks who do not necessarily understand the creative side of the development process.

I mean publishers expect a clear answer from you, but you’re just not there, not sure yet. They are asking you when the game will be released. I used to say, in a year.

Right now, I know very well what the game is about, how to market it, which platforms it should come out on. These things started dawning on me in 2020, when the core of the game was finished, and I already knew all my mechanics, all my story beats. And still, even after 2020, I have told publishers several times that the game will be released in a year or so. You can’t predict everything.

It took a lot of time to hone the gameplay and mechanics. It took tons of iterations and playtests to get them right. I also released two or three public demos that different players tried out.

Did Crytivo give you any feedback on the game? Were there any suggestions on how to improve it?

Oh yes! They have their own game designer, or maybe even a whole bunch. But back then, the project was still in its early days, I was just not ready for any external input. Any proposed changes I perceived as interference with my vision as an auteur.

When did it change for you? When did you feel like you really nailed the gameplay and could start having a meaningful conversation with publishers?

There’s a whole story to it.

I mostly promote Selfloss on Twitter, I have more than 6 thousand subscribers there. So I posted some nice GIF, and Geoff Keighley got in touch. I didn’t even believe it at first, he’s got almost 2 million subscribers. Anyway, he said, “Cool game. Do you have a demo?” He explained that his team was scouting for indie games to showcase at the 2020 Game Awards. Selfloss made it to the top ten globally.

I did have a demo at that time, but I didn’t like it. So I decided to completely overhaul it. I crunched for 2 or 3 weeks, sleeping for a couple of hours each day. I reworked a huge chunk of the game, and maybe it was the sheer amount of stress I was under, but somehow I got there. The pace, the flow was there. This was it, I thought.

I submitted this demo. Then there were several more iterations for various Steam festivals, and so by now, this version of the game has been played by about 12 thousand people, and in 90% of cases, the feedback has been extremely positive. People contacted me by email, on the Steam forums, on Twitter, on VK [formerly, VKontakte, a popular social network in Russia — Ed.]. They specifically praised the things that I worked on and that I improved. This was the turning point. From that moment on, I could really tell publishers that I had the vision and the gameplay. It was two years after the start of development.

Amazing that those publishers and Keighley contacted you themselves. But with indie devs, this is not always the case. You must have been doing something right. I wonder if it just happened like that, simply because you pursued a certain vision, which just happened to be so attractive? Or did you take steps to boost your visibility for publishers somehow?

For indies to survive in the modern world, the visuals must be top quality, they should have individuality. A soul should shine through. Everything has to be so cute you almost want to touch it.

It’s not exactly a guiding principle that I try to stick to. It’s just what I like to do. I am extremely picky when it comes to aesthetics. For each chunk of a level, I keep fiddling with the camera until I get the result I like.

And then I suggest you show off your game’s visuals on Twitter. If you are looking for a Western publisher, most of them are scouting on Twitter. It allows them to see right away if your game has a lot of likes, a lot of reposts, which means there is potential. That’s how Geoff Keighley found me. There was a tweet that got several thousand likes and several hundred retweets.

That is some tweet you posted!

Well, if you follow different developers on Twitter, you just learn what kind of tweets get the most likes from the gamedev community.

Speaking of GIFs, it has to be bright in most cases, not dark. There should always be some character in focus, there should be funny or cute animations, small movements like dangling, falling, etc. Generally, some element of physicality should be present, even if it is a stylized game. GIFs are this whole marketing asset and should be treated as such.

So the Game Awards gave you this global exposure, and a whole other period began in the life of Selfloss. Who started talking to you at that point?

Annapurna immediately got in touch. To be fair, I had emailed them myself long before the Game Awards. It is the most famous indie publisher right now, the most revered one. Almost every game they have published has won some cool award. At the BAFTAs or the Game Awards. It would be great to land Selfloss on the list of Annapurna’s games on their Wikipedia page — those were my thoughts at the time.

So the first time we communicated was before the Game Awards. The folks at Annapurna played the demo, which I hadn’t polished yet. I told them right away, “Sorry, guys, I am already reworking it.” Then we had a call, corresponded briefly, and they sent me an assignment. They asked me to write an essay about my game, breaking down game design mistakes I had made and how I was going to fix them. So I did. In a few days, I wrote an essay. First, it was ten pages in Google Docs, then I reduced it to three because I didn’t want to sound tedious.

They said, “Okay. Let us go over it and get back to you.” But they didn’t get back. I tried contacting them several times afterwards, intermittently, until I decided that, apparently, they did not like the game or something, that it failed to meet their standard. I thought it was the end of the story.

But when they found out that Geoff Keighley invited me to participate in the Game Awards, they were back in touch. Celebrities are like a magnet for big publishers, I think. If they see that Elon Musk is interested in you, they will most likely reach out to you.

So we started corresponding again. I sent them a new demo, and they said, “Cool. We are going to play it.” But for the second time, the communication also just kind of faded. I was completely despirited by that. I thought, “Okay, then. There must be something else they didn’t like.” Too bad I had no idea what it was.

So I have this big complaint about Annapurna. There was no feedback from them. I think it’s just good manners when a publisher, even a small one, gives you at least one page of feedback if they have asked you for a demo. Even if they don’t sign with you in the end. If you haven’t received any feedback, it should be the end of the conversation. Developer time is super valuable. You’ve sent them a demo, supplied all the necessary information, screenshots, and they have played it and not given you feedback? Blacklist them, full stop.

This is what I did with Annapurna. But just over a month ago, I signed with an investor, and their representatives were interested in Annapurna. When they found out that Annapurna was in touch with me, they were like, “Wow! Great! Let’s try to get through to them again.” So in the end, I emailed them again, “Well, what about that demo I sent almost six months ago? Did you play it?” And they answered, “Yes, we played it. Let’s schedule another call.”

And did the third call happen?

Yes, it happened. Ahead of the call, I sent them a detailed pitch deck on the so-called core pillars of the game, the fundamental principles the game is built on. And so we went through this presentation with them. I really liked that conversation because it was very substantial. They asked me, “What is the symbolism of that boat in your game?”, “How does it affect the game?”, “Why did you add it?” Or, “Why did you decide to add this kind of combat system, and not a different one, and why does the game play at this pace, and not at a different one?” We thoroughly discussed why everything was done the way it was done.

We talked, and they said that they had to take some time to think it over and that they would come back and say “yes” or “no.” It was over a month ago. I haven’t heard from them since.

By the way, right before that last call, they played the new demo again. And finally, they did give me feedback. But it was so basic, like “We didn’t find some aspects of the game particularly engaging. Best to rework them.” The thing is they did not even specify what these moments were, or how they thought they needed to be reworked. I got the impression they simply did not like the game, but didn’t want to admit it. Or maybe they are waiting for it to somehow take off on its own, and then they will be ready to get on board.

I would say it is unprofessional. Their feedback was useless. Why then even bother setting up all these calls during the year? I don’t like this uncertainty. Let’s just say my feelings for Annapurna have cooled down quite a bit.

Are they on your blacklist now, or will you give them another chance if your investors insist, or if they show up themselves?

It depends. There are several publishers right now that I’m communicating with, and Annapurna is not my priority at the moment. If things work out with another preferred publisher, I won’t need Annapurna.

And who is this other publisher?

I’d rather not say just yet, you know, not to jinx it. But so far, I’ve been happy with our communication. First, I liked that they had a lot of questions about game production. In this regard, they are similar to Annapurna. They, too, asked how these mechanics are made, how many levels there are, why these levels are designed like this. And, secondly, they just cut to the chase. “Here’s our forecast,” they said. And this is before any signings! “Based on what we have already released, that’s the amount of revenue we expect from your game, how soon, on what platforms.” For me, it is a good sign. Because all too often publishers would say, “Ok, we take 50% — let’s sign.” And you are like, “50% of what? 100 dollars?”

Actually, I want the publisher I’ll work with to be like those book publishers of the 80s, when there was still no internet. You enter into a partnership. It is not necessarily a loving and maybe not even friendly relationship. But it is a partnership in the sense that they should support you in every way possible , nourish your creativity. Because it’s in their best interests that you stay in a good mood, scribbling new books for them. Unfortunately, I’m yet to see an attitude like this. Maybe some publishers did try to act friendly and supportive, but it came across as insincere.

So the other publisher that you approached yourself was Versus Evil. Why them?

Because it’s The Banner Saga and, most recently, Yaga.

All their titles feature a fantasy setting, with knights, some Slavic flair, all that. I like it. I thought it suited me thematically. So I emailed them, “Hey, guys. I played all the Banner Saga games that you published. My game is just like that, but a different genre.”

They liked it. They liked it so much that an opposite situation developed here. They hurried me all the time. I had messages in my mailbox like “Here’s the deal. Think about it for a week and let’s sign.” And it wasn’t managers that talked to me, it was one of the executives at Versus Evil. I was not ready to make a decision so quickly. And thank God for that!

A piece of advice, if I may. Don’t be afraid to ask a publisher for revenue forecasts, sales figures, numbers of copies, etc. What do they expect? When do they expect it? I asked this question to Versus Evil, and what they told me was, “All games are different.” Of course, all games are different. But if a publisher is not prepared to offer at least a rough estimate of the minimum and maximum possible outcome, then, apparently, they simply do not want to talk about these numbers. It immediately alerted me.

And something else pushed me away.

I always tell publishers, “Whatever cut you take, it should be way lower for Steam, because I already have quite a number of wishlists there.” I’ve already done some UA heavy lifting for Steam. In my opinion, it is only logical that the publisher should not charge the same fee for the Steam version as it does for other platforms.

In that respect, Crytivo, for example, offered a good option. They have more than halved their cut for Steam compared to other platforms. I am very grateful to them for this, even though things didn’t work out between us.

So that’s what I suggested to Versus Evil, but they did not go for it.

Western publishers won’t agree to this. They’d be like, “Our marketing campaign covers all platforms, right? We can’t possibly ask users not to look at the Steam page, to only look at the Switch page. So we can’t reduce our publishing share for individual platforms.”

I see. So with Annapurna, you were interested in their reputation first and foremost, their brand. What did you want from Versus Evil?

I’m interested in everything publishers can offer except funding. I don’t need money. What I need is porting, localization, QA. I’d be happy to spare myself any headaches in these areas.

What about Raw Fury, for example? You never tried reaching out to them?

Nope. Take a look at the list of their games on Steam. You will see that in addition to hits, which have 10 thousand reviews each, there are a bunch of games with only 50-100 reviews. Meaning the latter ones weren’t marketed at all. That’s something of a trend with many popular publishers. You can’t rate these publishing darlings like Raw Fury by their well-known games alone. Look at how many games they publish per month, you’ll go nuts. Out of ten games they release, only one really takes off, and all the rest will sink into oblivion. I talked with people who published with them, and they confirmed this.

Roughly speaking, that’s what they do: each month, there is a million dollars allocated for marketing ten projects, and the publisher initially gives everyone a thousand bucks. They see which one takes off and give them 990 thousand. And to everyone else, the publisher simply says, “Sorry, guys, it hasn’t worked out with you. But you will still owe us money… You’ll be giving us 50% of the hundred bucks you make each month, until the end of your days.”

So you didn’t interact with Raw Fury at all?

No, not when working on Selfloss. I did talk with them, though, when I was making my previous game, Mechanism. They played the demo and gave some very good feedback. I don’t remember the specifics, but they rolled out this whole document with feedback. The general idea was that my game was too depressing, that it was not their type of game. Recently, they’ve started making games that are more wholesome, more artsy. But a few years ago, this was not the case. I remember all the hype around The Last Night, and they wanted more stuff like that. Something cyberpunk-y or fun in the style of Fall Guys.

What about the publishers that contacted you themselves?

Among the publishers that contacted me was, for example, Daedalic. They emailed me this summer. They were very interested in the game. They played the new demo and liked everything about it.

Yay!

Not really! I spoke with several teams that worked with Daedalic — their feedback was overwhelmingly negative. So I never even considered them.

There were, though, other publishers that I did consider, but they were just not flexible enough.

You see, many publishers absolutely have to stick to this scheme when they first invest in you, then recoup it. But what if I don’t need it? I already have my investors. I would tell these publishers, “Let’s forget about this invest-and-recoup crap. Why can’t we just pay you for your publishing expertise, and that’s it? Sure, you’ll get some share of sales revenue, you’ve got to make money somehow.” But they would often insist on this invest-and-recoup scheme. They are like, “We just need some kind of fixed payment for our work.” I mean, they don’t just recoup what they spend, it comes with a multiplier, obviously.

I hate this. It’s like you approach a person who’s really good at marketing and tell them, “I have a million dollars. Make me something cool for a million dollars.” And they say, “No. Here’s what we are going to do. I am going to spend my million dollars, and then you are going to give two million dollars back to me because I need to recoup my expenses and make a profit.” It just drives me crazy. I mean, I’m fortunate enough to be an indie with money. I don’t need you to invest in me. Why can’t I just pay you so that you do your thing?” The truth is, lots of publishers just don’t care whether you have money or not, you’ve just got to owe them something. It really pisses me off.

And do you know what the best part is? A lot of these publishers don’t even do anything themselves! They just have connections with a bunch of different small agencies. One of them does marketing, the other one ports games, the third one localizes them. So the publisher takes your money, outsources everything, and you are lucky if they assign a manager to your project who would control all these other businesses.

That’s depressing. Any other publishers that deserve a mention?

Another one that emailed me was HypeTrain Digital. These guys are great, of course, in the sense that all the latest games that they have released are selling very well, as far as I understand. So I am not criticizing their marketing or publishing skills. But when I just started making Selfloss, HypeTrain was also interested, and I sent them a demo, and they just never got back to me. My friend had exactly the same situation with them! He sent them a demo, they played it, after that — radio silence.

Fifty companies have communicated with you. Have you thoroughly researched each one of them? Or have you already developed an intuition and you just see right away who’s worth talking to and who’s not?

It’s actually quite simple. If a publisher gets in touch with you, go to their website and find out what games they have released. Don’t look at their sales right away, just see if their games are somehow similar to yours. Any publisher with serious ambitions maintains a certain image, thematically and genre-wise. Annapurna has that image, so everyone knows about Annapurna. Raw Fury has it, and that’s why everyone has heard about Raw Fury. The same is true about TinyBuild and HypeTrain.

With their games, you can trace some recurring stylistic accents from title to title. I think it’s a smart thing to do for a publisher if they are going to have at least some kind of future. Because, honestly, I don’t really believe that there will be a place for publishers in the future. Not in the traditional sense of the word, anyway.

So if you see that there’s no consistency stylistically among the publisher’s games, it probably means you’re dealing with a new publisher and they just randomly publish whatever games come their way. I wouldn’t risk my project with a publisher like this.

If, on the other hand, I see that all the games from that publisher follow a certain stylistic pattern and, importantly, it matches my game, and if I immediately recognize at least one of their games because I’ve seen it somewhere, — well, then it’s probably ok to schedule a call with these guys and have a conversation.

And then, when you actually meet them, online or offline, you just like some people more, some less.

And if it’s the latter, what do you say? That you are not ready for a committed relationship?

With most publishers, it’s not like I expressly say no. I just stop answering. First of all, it’s hard to handle the constant stream of incoming emails and calls. Secondly, as a rule, it’s just a matter of time before a bigger, more interesting publisher shows up, and then you just switch to them. I haven’t exactly figured out a way to always dish out rejections tactfully. Sometimes I give a direct answer. Like when I was in talks with Versus Evil and Annapurna at the same time. I just told Versus Evil that I was also talking with Annapurna, who I would pick over them if they offered good conditions. So yes, sometimes I just tell publishers right away, “Hey guys, there’s another preferred candidate, but if things don’t work out with them, I’d consider you.”

How do people take it?

Well, it’s not the nicest thing to say to a person, I guess. Then again, I don’t see anything wrong with it. If the guys from Annapurna told me, “Sorry, man, we have our eyes on a game that’s better than yours,” I’d say, “okay,” it doesn’t bother me that much. In fact, sometimes publishers themselves ask me if I’m in touch with anybody else at the moment. I’m always honest. I tell them that there’s someone else and how serious it is with them. I mean if they choose to be direct like this, for me, it’s a sign of an honest publisher, which means it will be easier to communicate with them in the future.

Aren’t you concerned, though? We will post this interview, in which you admit that you stood up half of the publishers because you didn’t have time, and the other half you don’t exactly describe in the best way. Aren’t you afraid they will blacklist you?

I believe that until we, creators, developers, start talking openly about these things, publishers will keep charging these insane fees. Publishers almost always charge 50%.

There was a time when 30% was the norm, or so they say. Like Steam took 30%, your publisher took 30%, and then you had the remaining 40% all to yourself. But that hardly ever happens anymore! For a publisher to agree to a 30% cut, I don’t know how incredible your game must be. All prestigious publishers will take 50%, if you already have a game that looks really good. If your game is not outright stunning, then they will take all 70%.

So yeah, as long as we all keep praising or criticizing publishers anonymously, they will continue ripping us off. Anonymity needs to stop completely, so that fledgling developers know who is worth communicating with, and who’s not, and what to expect.

Wouldn’t it be great if developers just shared what conditions publishers offer them, what their forecasts are? I’m not asking to disclose the actual sales figures, just the forecasts for their games! Wouldn’t it be extremely useful?

I’m only saying this because publishers themselves tend not to disclose this information. It is one of the red flags for me when communicating with a publisher. I see their game and ask them right away, “How much did it bring in?” They often say, “We can’t talk about it.” What a load of BS. There are publishers who have no problem talking about it.

Again, I am not even asking for specific figures. Just tell me how many units it sold approximately, across all platforms in a year, so that I can decide whether it is enough money for me to live on and start my next project. If the publisher keeps that information from me, what should I assume? I assume the game sold poorly, and they are ashamed of the result.

If the publisher can share the figures, I can at least venture a guess. “This game is similar to mine. They published it not very long ago. I can probably expect similar numbers.” How else can you, as a developer, figure out how much you will make? There are no other tools.

So I think we should take away all anonymity from publishers. It is in our best interests. Publishers are nothing without developers. If there are no developers, how will game publishers make money?

Listen, about that investor of yours? How did you meet them? Publishing services aside, it’s funding that a lot of devs want from publishers. So what’s your situation exactly?

I hate to bring up politics. But that’s the way it was. I asked a friend who works at Epic Games, “Listen, the political situation in Russia kind of scares me. How can I set up a studio abroad and leave the country and make games outside of Russia?” And I mean, after the situation in Belarus this summer, I really started thinking about it. I have lots of friends among developers, at Wargaming, for example, who used to live in Minsk. Thank God, most of them were able to relocate, but it bothers me, you know? I realized that I do not want to make a career here because it is not safe.

So my friend from Epic Games said, “Listen, we were recently approached by an investor who asked for advice on interesting indie games. Let me put you in touch with them.” And that’s how it all started.

The guys from Epic Games really talked me up. They said that my studio is basically just this one wholesome dude, it’s not 50 people. It will be very easy to work, it’s a very controlled production setup, when you have this cozy little company that will release its uniquely minimalist stylized games. They made it sound so nice that everything went really smoothly with the investors.

In general, I think it is the future. There will be no publishers, only investors. Want to know a secret? When I’m talking to big well-known publishers, they tell me right away: “In two years, we will probably become investors, and if your game performs well now, we may be ready to invest in you in the future, to become partners.” With big publishers, it’s already happening, this change, when they start investing, rather than doing the publishing per se. That’s what Microsoft is doing now, snapping all these studios, including indies.

It’s already happening, yes. Publishers investing in studios. What about Selfloss, though? If it doesn’t work out with your preferred candidate, are you ready to release it without a publisher?

Oh, I’m ready. Not sure about my investor. Haha. Sure, if the publisher’s forecasts or their fees don’t look good, we’ll just go our separate ways. It’s either going to be another publisher, or self-publishing.

And that’s another trend that I’m seeing these days. Many devs are choosing not to work with publishers as such. Instead, they contact marketing agencies, porting companies, and localization companies. I’ve done it. For my projects, I just commission translations from companies that are focused on game translations.

The same is true for marketing. The beauty of it is that you just pay an amount — and that’s it. Your contract ends there, you are no longer involved with that company. No fees, no royalties, no rights, no anything. You paid 10 thousand dollars, they provided marketing services worth 10 thousand dollars. Or maybe they didn’t. Then you’ll have to deal with it. Many developers are simply afraid. “How can we communicate with these companies? What do we even ask?” I believe, one way or another, if you launch even a small game company, you will have to learn this stuff. It is an important experience to have in this industry. There is no escaping this. But then, if you learn it, it becomes a matter of personal choice for you: if you want to spare yourself any headache, just go to publishers and hope that they will do everything right, or perhaps you are ready to take matters into your own hands.

Publishers often say in cases like this, “We will take care of everything, and you can just do your thing, which is creating, being creative.”

I’m super creative, but I still think I need to understand all the processes. If it doesn’t work out with a publisher, I can always hire a specialized agency that provides a specific service. It’s not even that expensive, sometimes it’s ridiculously cheap. Porting can cost you up to $10,000 for all platforms. Well, these will not necessarily be the best ports in the world. And of course, even with this kind of money, you’ve got to get it somewhere. A lot of indies only have 10 thousand to spend on the whole game. But that’s where this mixed approach comes in handy. Find an investor. Or a publisher turned investor. They have the money, they have the expertise, all of which they will give to you. And you, as the leader of your studio, will decide how to use it. That’s how I imagine spending the next 15-20 years of my life as a game developer.

Correction

Nov. 02, 2021

An earlier version of this story listed Daedalic among publishers that would invariably insist on investing in a development studio, regardless of whether it requires funding or not. This has been amended to not state anything on the nature of Daedalic’s contracts.