Baldur’s Gate 3 has finally launched today, and Larian Studios looks stronger than ever — both financially and creatively. However, the company has overcome many headwinds in its nearly 30-year history, from crises to publishers that couldn’t care less about the team and their passion.

Ultima VII, Larian’s origins, and the FUME scale

We won’t dive deep into the creative journey of Larian Studios, as there are plenty of great articles written about it. But before we get into the financial challenges the company has faced on its way to success, it is worth saying a few words about Ultima VII: The Black Gate, the legendary RPG from Richard Garriott and Origins Systems that shaped Larian and its founder Swen Vincke.

Vincke’s obsession with Ultima VII is no secret. In fact, he talked about the game so much in different interviews (and is still being asked about it) that this became sort of a meme in the community. However, one fact cannot be denied: this particular RPG and the series as a whole inspired so many creators — from Raphael Colantonio (Arx Fatalis, Prey, Weird West) to Todd Howard (The Elder Scrolls, Fallout 3-4) — that it is now basically your favorite developer’s favorite game.

Ultima VII: The Black Gate

For instance, here is how Vincke recently described what made Ultima VII so special and how it influenced his approach to game development:

It was just a sheer sense of reward for exploration. I picked that up from that game and said that this is one of the games that rewards exploration so much through systemic interaction with the world, because you have to put your little crates next to one another and climb on top of it to get through things, and there were secrets everywhere. I loved it, and it has heavily defined how I think RPGs should be made because I want to get that same feeling from our own games.

founder of Larian Studios

So reward for exploration and systematic interaction are the two main things that Vincke has always wanted to implement in his games. Even when he started Larian back in 1996, with no background and only a couple of friends on board, the ambition to create his own ultimate role-playing experience was already there.

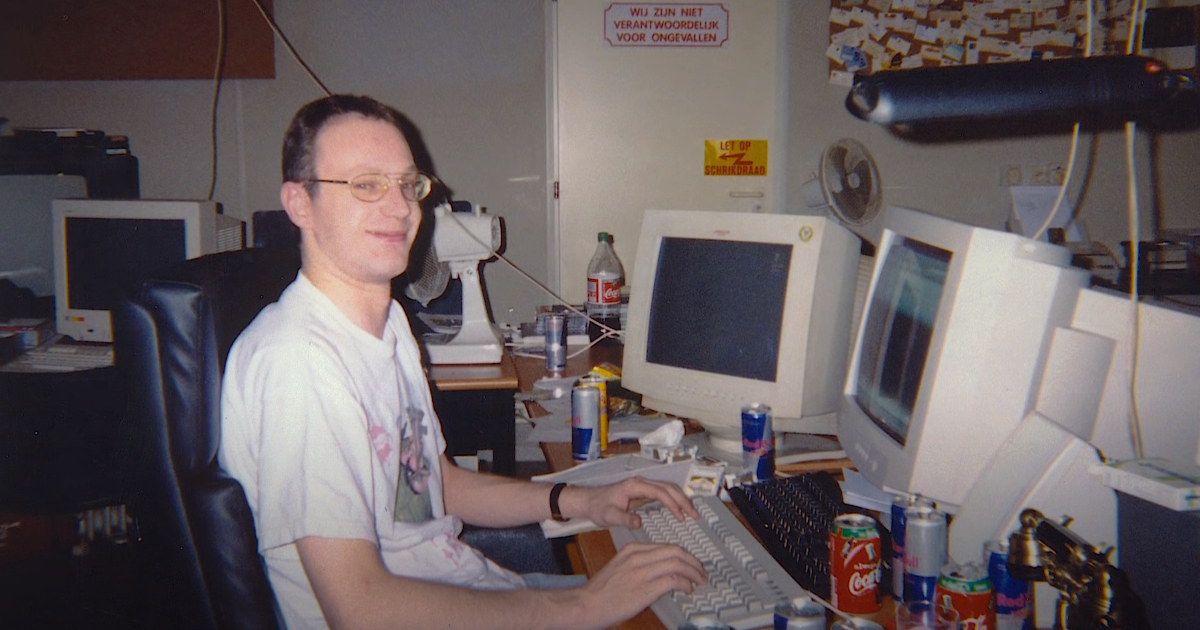

Swen Vincke during Larian’s early days (Source: Gameumentary)

The team had nothing — no industry knowledge, no funding — except for the vision of what a truly great game in the genre should look like. Years later, Vincke came up with his own scale to evaluate the likelihood of him falling in love with an RPG called FUME:

- F — Freedom of character development available;

- U — Universe in which the player develops their character;

- M — Motivation that is given to the player to develop their character;

- E — the quality of Enemies against which the player can develop their character.

This doesn’t mean that all RPGs should be rated on this scale, but it does give you a glimpse into Larian’s approach to assessing the quality of its designs and concepts. According to Vincke, anything that lowers the FUME potential of the studio’s games — no matter how well that particular mechanic has proven itself — should ideally be eliminated.

I haven’t encountered a single game which scores high on all fronts, but I did enjoy many games that score moderately well in at least one aspect, so any game that combines two or even three components of FUME is in my opinion already a pretty successful RPG. If you want to know why I loved Ultima VII so much, it’s because it scored high on Universe and Motivation, gave me sufficient illusion of Freedom and I at least remember some of its villains.

founder of Larian Studios

Aside from Ultima VII, another game with a pretty high FUME score is Fallout 2, but most RPGs out there, in Vincke’s opinion, are a far cry from what he wants to see in the genre, especially in terms of freedom. “I’d love to include a modern RPG here, but sadly there are none that I played that score as highly as those games did,” he said in 2013.

So if you don’t have an RPG in the market that you truly enjoy, make one yourself. And Larian really tried! But it always had to make certain technical, production, and financial compromises that accompany any independent studio when developing a game. There were so many pitfalls along the way that the world could never have seen the success of Divinity: Original Sin 1-2 and the freshly released Baldur’s Gate 3, which may indeed be the title with the highest FUME score in the company’s history.

Baldur’s Gate 3

Ragnarok Unless → The Lady, The Mage & The Knight → first financial problems

Before the first official Larian office was established in a small electronics shop in 1997, the team was working on a game called Ragnarok Unless. Although Vincke later joked that the name was stupid (some sources even say the original title included an ellipsis), it was an ambitious open-world RPG inspired by… Ultima VII, you guessed it.

In 1996, Vincke and his friends went to the ECTS, a European trade show similar to E3, to pitch their project. “We were just a bunch of guys hammering around at Intel 486s in an apartment. We had an idea that if we presented ourselves as a studio we’d get a big cheque for it,” he recalls.

This is exactly what happened, as Larian managed to get the attention of Atari that gave the team their first contract worth $50,000. When it seemed that things were going uphill for the young studio, Atari decided to ditch the PC market and eventually merged with disk-drive maker JTS.

So the studio went from signing a $50k publishing deal to having no money to make its big dreams come true.

Sketch for Ragnarok Unless (Source: Gameumentary)

Although one of Vincke’s friends left the team after that, he personally had no plans to give up. Larian used some of the ideas from Ragnarok Unless to make another RPG, The Lady, The Mage, and The Knight.

The problem was that a project like this was difficult to pitch, not only due to the scope of its ambitions (three playable characters, huge focus on exploration, etc.), but also the fact that Larian still had no track record of released titles. So the team decided to make a smaller game, an RTS called L.E.D. Wars, which was developed in just five months.

Fortunately, the studio managed to sign both projects at once. L.E.D. Wars, distributed by Ionos, came out in 1997 as the first game Larian actually finished, and The Lady, The Mage, and The Knight was to be released by German publisher Attic Entertainment (Realms of Arkania).

The Lady, The Mage, and The Knight

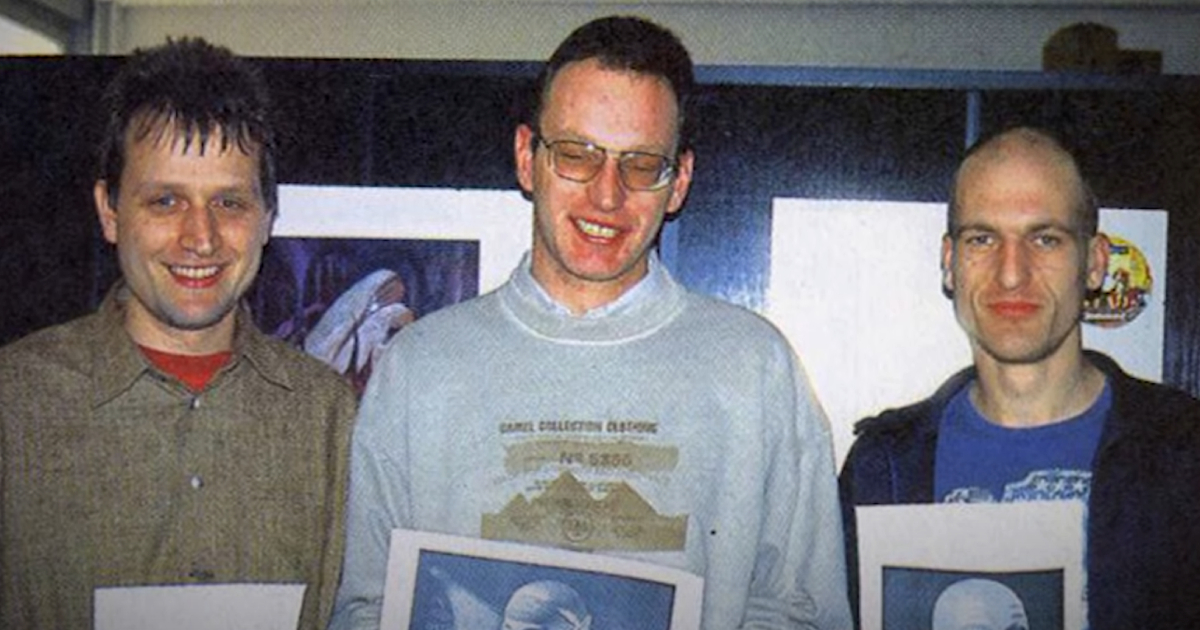

Larian was optimistic and started expanding its small team, but fate had other plans for the studio. The Lady, The Mage, and The Knight was an 8-bit game, and Attic Entertainment suddenly demanded that the studio redo all the assets after it attended E3 1998 and was impressed with Diablo II‘s 16-bit color graphics.

The publisher said it would only fund the title if Larian agreed to change its setting to The Dark Eye, a tabletop RPG world aka the German version of Dungeons & Dragons. To help the team translate The Lady, The Mage, and The Knight into a 16-bit game, Attic sent a bunch of its in-house developers to the studio.

The twist? In 1999, the publisher ran out of money and simply couldn’t pay Larian anymore. “We suddenly found ourselves not only with our own team, but also now with the German team that we had to pay for, and we needed to figure out something,” Vincke said.

Swen Vincke (center) with Attic co-founders, Jochen Hamma and Guido Henkel (Source: Gameumentary)

Vincke was left with a team of 30 people he was responsible for. As he recalled in the Gameumentary film, the studio was “literally one month away from closing.” The only way out was to make work-for-hire projects, and Vincke said Larian developed around 20-30 smaller games for other companies that year alone.

Avoiding bankruptcy not once, not twice… Has Larian ever been confident in its future?

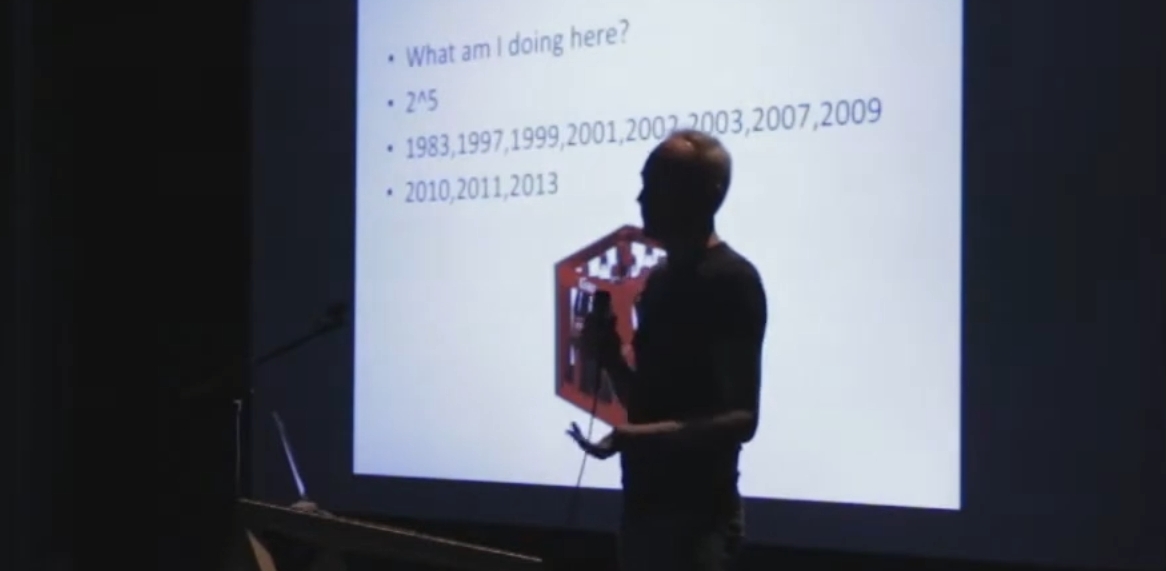

If you think that Larian got back on its feet after surviving the stressful 1999, below are all the years when Vincke “almost went bankrupt trying to make games and getting them published.” This image is from his talk at the Screenshake 2015 fest, meaning that Larian was on the brink of bankruptcy at least 10 times between 1997 and 2013.

Seems like a wild ride, to put it mildly!

The only exception here is 1983 as the year Vincke started making video games

As Vincke pointed out during his 2019 GDC talk, “Larian has always been a company that tried to reach for the sky and often crashed, and that’s where all the bruises come from.”

One of the toughest periods in Larian’s history was between 1999 and 2003, and it pretty much sums up the studio’s problem with publishers and why it doesn’t want to work with any of them anymore.

Having survived on work-for-hire contracts, the company used the canceled The Lady, The Mage, and Knight as the foundation for its new game, Divinity: The Sword of Lies. Although Vincke cared most about the narrative and world exploration, the only way to sell it to a publisher was to pitch it as an action RPG with a Diablo-like hack-and-slash combat.

Divine Divinity

That’s how Larian signed with German publisher CDV Software. And there were a whole bunch of problems — from the publisher coming up with a stupid title “Divine Divinity” (following the success of Sudden Strike, it believed that all its projects should have alliteration) to the game shipping in an unfinished state with tons of bugs. As Vincke told PC Gamer, Larian learned after the fact that CDV started selling the first Divinity in Germany in August, 2002.

I discovered that Divinity was being released when I was doing a press tour for it in the US. We were horribly late with it, at least by a year, but we still needed some time to polish it. So it shipped with 7,000 known bugs, and the initial reviews obviously focused on them. But as we started tweaking it, people started seeing that it was a good game.

founder of Larian Studios

Divine Divinity wasn’t a masterpiece, but bugs aside, it was a good game that just needed more time for QA and polishing. It ended up doing really well commercially, but Larian received no money from the sales. “It was a standard contract back in the day, but if you didn’t sell millions of your game under the royalties model it was very hard to earn any money out of it,” Vincke said.

As a result, Larian almost went bankrupt again, going from 30 employees to just three by 2003. According to Vincke, it hurt because he had to almost close the studio: “No money coming in, critical success everywhere, and an empty studio. It was a very hard time. I almost cracked then, but I didn’t.”

Larian survived against the odds, returning to the work-for-hire practice to fund the development of the next title, Beyond Divinity, and gradually expanding the team to around 25 people. The goal was to finally earn some money from the game, and this time, Larian also tried to negotiate with distributors directly to avoid falling into another publisher’s trap. The deal the studio made involved minimum guarantees, meaning that the distributor agreed to buy a certain amount of physical copies upfront.

Beyond Divinity

On top of that, Vincke signed a contract with Belgium broadcaster Ketnet to make KetnetKick, a video game/creative studio that allowed kids to make simple movies and cartoons within the 3D world with a chance of being shown on TV.

So financial stability was briefly there, and while Larian considers Beyond Divinity to be the worst game in the series, it had some ideas that were used in later titles (including the Original Sin series). And a return to work-for-hire projects allowed the studio to pay the bills and fund its next game.

KetnetKick

Failed launch of Divinity II left Larian in dire state

Having enough money to make a full-fledged Divinity sequel, Larian managed to get a license for the Gamebryo engine (TES IV: Oblivion). To seek additional funding and ship Divinity II: Ego Draconis, the studio returned to CDV Software and partnered with another German publisher, DTP Entertainment.

The game was set to become Larian’s truly next-gen RPG, but the production was filled with obstacles and there was a huge attrition on the team. Larian executive producer David Walgrave recalled that many young developers saw working at the studio as a bit of a risk, and some people even “couldn’t get a loan from their bank because they were working at Larian Studios.”

Divinity II: Ego Draconis

Ego Draconis was an open world RPG in full 3D with a lot of ambitious mechanics like the ability to turn into a dragon. Larian just needed enough time to make everything work properly, but then the crisis hit, and DTP Entertainment, which was running out of money, demanded that the studio ship the game as soon as possible.

As a result, Divinity II launched in 2009 with a lot of technical issues and unfinished ideas, and the Xbox 360 version became the lowest-scored game in Larian’s history — only 62/100 on Metacritic. Although the studio eventually managed to make an improved and more comercially successful version, The Dragon Knight Saga, the damage was done.

We've pretty much lost everything that we've built up financially over the last years. Half of my team is looking to go work for EA or Activision. We're not getting paid at all from the publisher. My wife doesn't want to talk to me anymore and she wants to move. I'm a physical wreck, and a doctor tells me I have to take another job. So there we are... 2009. It wasn't really good.

founder of Larian Studios

This was a really dark time for Larian, which was left with little to no chance of surviving the crisis. The only salvation was to completely reshape its business approach to never ever work with game publishers again and become a truly independent studio.

Vincke approached the team with a presentation detailing what the next chapter of Larian Studios would be. It was focused on Time, Quality, and Budget — three things that most developers struggle to balance while making their games. That’s where all the compromises usually come from.

At the time, the only element Larian had complete control over was Quality. Vincke believed that the studio had to make every effort to improve the quality of its next game. But in order to do this and survive, the company needed Budget coming from a source that wouldn’t limit its Time and rush production.

Divinity: Dragon Commander

Vincke knew that it was time to say goodbye to publishing contracts, so work-for-hire projects remained the only stable source of funding. But it wasn’t enough to keep the company afloat while implementing a new ambitious strategy. So following the success of Dragon Knight Saga, Vincke managed to get VC funding for Larian’s next two games, Divinity: Dragon Commander and Divinity: Original Sin.

Production on the two titles started simultaneously, but Dragon Commander, a rather unusual mix of action, RPG, and strategy genres, was planned to be released first. The idea was to pour all potential money from the game (having no publisher this time meant that Larian collected all the revenue) into Original Sin, which was supposed to become an RPG the studio always wanted to make.

And that’s when Early Access and Kickstarter kicked in…

Divinity: Original Sin

Getting Time and Budget to increase Quality

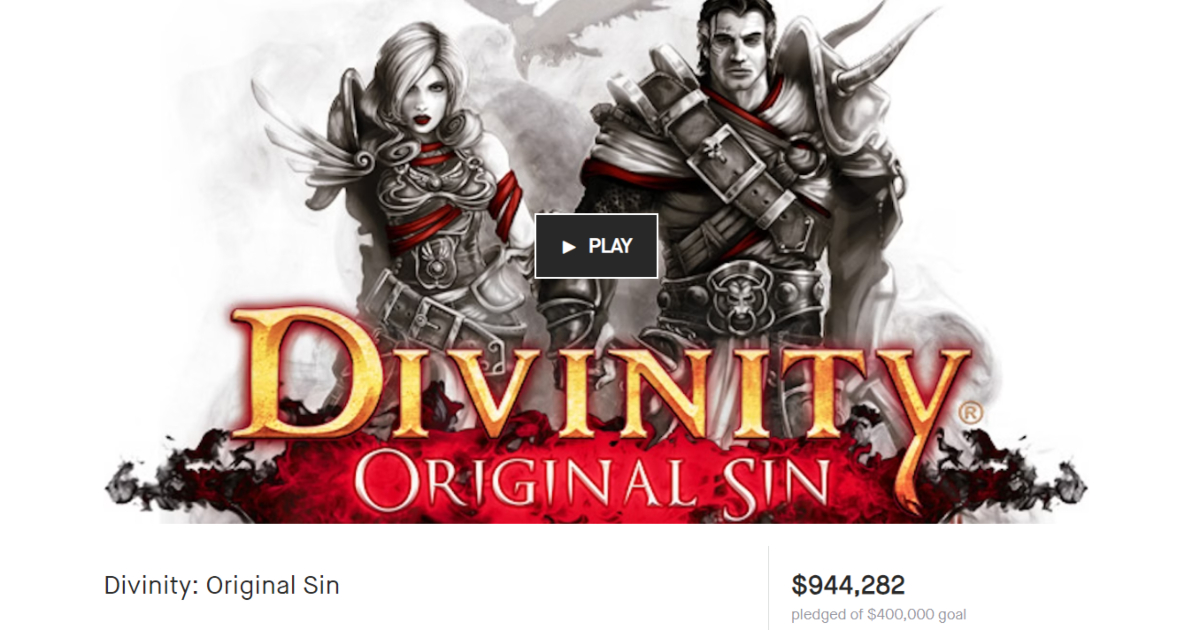

Larian launched a Kickstarter campaign for Divinity: Original Sin in 2013, raising nearly $1 million, well over the initial goal of $400,000. This was also a year when Steam introduced the Early Access model allowing players to buy promising yet unfinished games and support developers.

So the studio basically tried two new tools that eventually formed the basis of its approach to developing and releasing its projects going forward. Vincke believes that Early Access is a good model, but the game has to be big enough or have a lot of content that would still be fresh on release.

Kickstarter and Early Access combined gave us what I afterwards realized was the most important thing. It gave us time to finalize the last phase of the creation of a game. We've always been good at coming up with ideas and prototyping them, but we've always sucked at actually finishing them. By putting the games on Early Access, we certainly had the time to see what the players were doing with the features that we put in there, to see what's wrong with them, and to actually spend the time on polishing things.

founder of Larian Studios

This brings us back to those three core elements of every game development, and the crowdfunding model finally gave Larian enough Budget and Time, while EA allowed the team to keep improving the Quality of Original Sin based on real-time feedback from early adopters.

Kickstarter page for Divinity: Original Sin

Larian bet everything on Original Sin, with Vincke saying that the studio didn’t want to cheat on Quality at all, no matter how much budget and time it would take to finish the game: “Every single thing, down to my house to my mortage, everything that I had went into Original Sin.”

Of course, things didn’t go as planned. Larian hoped to build the game on a €3 million budget, but the total eventually increased to €4.5 million, meaning the studio once again could end up on the verge of bankruptcy.

Fortunately, the high risks paid off. Launched in June 2014, version 1.0 received an 87 Metascore. Larian then worked hard to release a much more improved Enhanced Edition, which got an average score of 94. It was a success, with over 500,000 units sold by September 2014. In 2019, Vincke said that Original Sin has sold around 2.5 million copies globally, which is an impressive result for an RPG made by a relatively small indie studio.

The huge success of Divinity: Original Sin 2 turned Larian into a global indie developer

With the Original Sin sequel, Larian decided to follow a similar business model. The studio raised over $2 million on Kickstarter and went through another Early Access. Divinity: Original Sin 2 became a hit, selling over 1 million units on Steam in the first two months since its launch in September 2017.

In a recent interview with Eurogamer, Vincke noted that the game’s lifetime sales across all platforms were three times the sales of the first Original Sin. He didn’t disclose the exact figures, but it were “enough to sustain something like [Baldur’s Gate 3] and allow us to develop it.” We may only assume that Original Sin 2 has sold over 7 million copies (based on the aforementioned data from 2019). Nevertheless, it was the game that proved that there was a market for RPGs with complex systems and huge levels of interaction with the world.

Divinity: Original Sin 2

Original Sin 2 was a turning point for Larian, as it started opening new offices across the globe and expanding its headcount from roughly 40 people to a team of 140 (as of 2017). Perhaps for the first time in its history, the company had sufficient resources and financial stability to take a new leap.

Thanks to the success of Original Sin 2, Wizards of the Coast approached Larian and gave it a license to the Dungeons & Dragons IP. The studio had everything: the budget, the time, and vast experience to produce a quality game based on the renowned franchise. The only thing Larian needed to make a worthy sequel to the legendary RPG series was to hire more talent.

Baldur’s Gate 3

During his GDC 2022 talk, Vincke noted that the company has now expanded to over 400 people, although he never thought his new project would require such a large team. From a small room in an electronics shop, it has grown into a global game developer with six offices in Ghent, Dublin, Quebec, Kuala Lumpur, Guildford, and Barcelona.

There was a moment where we started understanding what we needed to do to make this game. We thought we understood. Then we actually really understood. And so we had two choices: we could scale it down, or we could scale ourselves up. And so we chose to scale ourselves up.

founder of Larian Studios

Baldur’s Gate 3 went into Early Access in October 2020, spending nearly three years in beta. Speaking of early sales, Vincke said, “It’s vastly more successful than DOS2. You can’t compare it. I think it’s five-times in early access, if not more.” The hype is going to get even bigger with today’s global launch, but Larian seems to be confident in its most ambitious and large-scale RPG to date.

Last month, Baldur’s Gate 3 even caused debate in the gamedev community about whether it should be considered a new standard for the genre or if it is just an anomaly in today’s market. Some developers appealed to Larian’s unique combination of resources, vast experience, and tools that most studios don’t have. While there is a deal of truth in it, the company walked a bumpy road to finally be in the position it is today.

Larian is not the only studio that has struggled financially while pursuing its ambitions. However, it survived thanks to the team’s passion and Swen Vincke’s firm belief that one day his company would be able to make its own dream RPG without compromising Quality.

This doesn’t mean all games in the genre should be measured against Baldur’s Gate 3, as the standards are constantly changing and not everyone has to agree with Vincke’s vision of what makes role-playing games fun in the first place. But Larian definitely deserves applause for staying true to itself for over two decades already while maintaining independence with full control over its creative work and resources.