Canada is home to the third-largest game development workforce in the world, following the U.S. and Japan. That’s owing to the country’s vast talent pool, which is partly drawn here by the lucrative tax relief for devs.

During the recent PC/Console Game Developer Day Canada, we caught up with Pierre Moisan, Senior Advisor New Media, CEIM (centre d’entreprises et d’innovation de Montréal), to discuss the country’s gamedev scene and the opportunities and challenges it offers.

Pierre Moisan, Senior Advisor New Media, CEIM

Oleg Nesterenko, managing editor at GWO: Pierre, let’s start with several words about yourself, even though it means seriously compressing your 25+ years of experience.

I used to be a lawyer. I specialized in international trade contracts for transfer of intellectual property. It might sound very distant from video games, but the contracts I dealt with are actually almost identical to publishing agreements for a gaming IP.

In 1994, I worked for a client company called Megatoon, and we signed a major deal with WordPerfect for CD-ROMs that were very popular then.

I joined Megatoon and then we grew the company to become the biggest independent studio in Canada at the time. It became Behaviour, which is still around and still the biggest [this is despite the fact that the title of the biggest indie studio was temporarily claimed by Frima around ten years ago — Ed.].

Then I founded a few indie studios. And after that, I joined Ubisoft to help launch their Quebec City office. After Ubisoft, I joined a small company called Frima, which only had 12 employees back then. We grew it to 450 employees to become Canada’s biggest indie studio [outgrown by Behaviour around five years ago — Ed.]. Fast-forward nine years, I sold my shares and became the senior advisor new media at CEIM, supporting indie studios from all over Canada, organizing trade missions around the world for them and dealing with publishers. That’s a long story short.

Your story underpins that people of all walks of life can become part of this industry. Let’s talk Canada. It’s common knowledge that Canada is one of the best countries to make video games. What makes it such an attractive fiscal and legal environment for gaming companies?

It started with a very courageous decision by the government of the province of Quebec back in 1999. At the time, some people thought it was crazy. The decision was to offer tax credits to foreign video game studios that would establish an office in Quebec. The first studio to come in and benefit from the tax credit was Ubisoft. The local studios saw that and said they wanted it, too. So the government spread the tax credit to everybody and then started to actively invite big studios like Warner, Electronic Arts, and Square Enix, which all came. It created this whole game development ecosystem. At the same time, the schools, the universities jumped on board and started teaching students to draw, to code, to animate.

So, big studios came. Schools delivered the qualified manpower. Other provinces imitated the tax credit that Quebec had, which is now 37.5%. It spread to Ontario, British Columbia, Nova Scotia and others. So now Canada is number three in the world behind only the United States and Japan. We have around 600 studios and about 40,000 employees. They bring in 4.0 billion Canadian dollars to the economy.

Also, some people say that Canadian winters help. It’s so cold outside, we just sit in front of our computers coding and animating. You know, Oleg, what I am talking about!

Well, yes! Very cold winters here in Russia. But that didn’t prompt our government to implement any of these robust incentives for devs. Not until very recently, anyway. And it’s not that our gamedev community is not vocal! So, what is it, would you say, that made Canadian politicians far-sighted enough to deploy these policies in the first place?

Sometimes, circumstances can help. Years ago, before the tax credit, the economy was very bad. The main street in Montreal is called St. Catherine, but we used to call it Plywood City because so many stores were closed, windows covered with plywood to protect the glass.

The economy being so tough, there was this visionary guy called Sylvain Vaugeois. He came up with the idea that we should subsidize technological jobs. He argued this was the most promising field. And it was Vaugeois who went to meet Ubisoft, and he said something he was not allowed to say, but he said it anyway. He told Ubisoft: “If you come, we’ll subsidize half of your salaries.”

Ubisoft then was a small firm based in the Brittany province in the north of France. The Guillemot brothers were distributing foreign titles and were just starting to make video games. They had just released their first hit game Rayman. And they agreed to come.

Rayman (1995). Developed by Ubisoft

So Vaugeois came to Bernard Landry, the premier of Quebec, to whom he was very close. And Landry put pressure on the federal government, and the federal government said, “Let’s do it!”

The industry needed this kind of representation because before that, people didn’t really consider video games a technological field. Nor did they consider them as having cultural value. So video games couldn’t benefit from the support countries give to cultural institutions or technological businesses. Luckily, this mixture of circumstances and enlightened leadership took shape in Quebec, sparking change across all of Canada.

So you have tax relief support at the provincial level, at the federal level. There must also be funds willing to finance game development directly.

There is a very good program called Canada Media Fund (CMF). They set up this competition that you can win if you can be original and different. And this is what VCs or bankers are not interested in.

If you say I’m going to do something that has never been done before, bankers will ask to first show evidence that people like it and maybe give you money after that. But we don’t need money afterwards, we need money upfront to develop games.

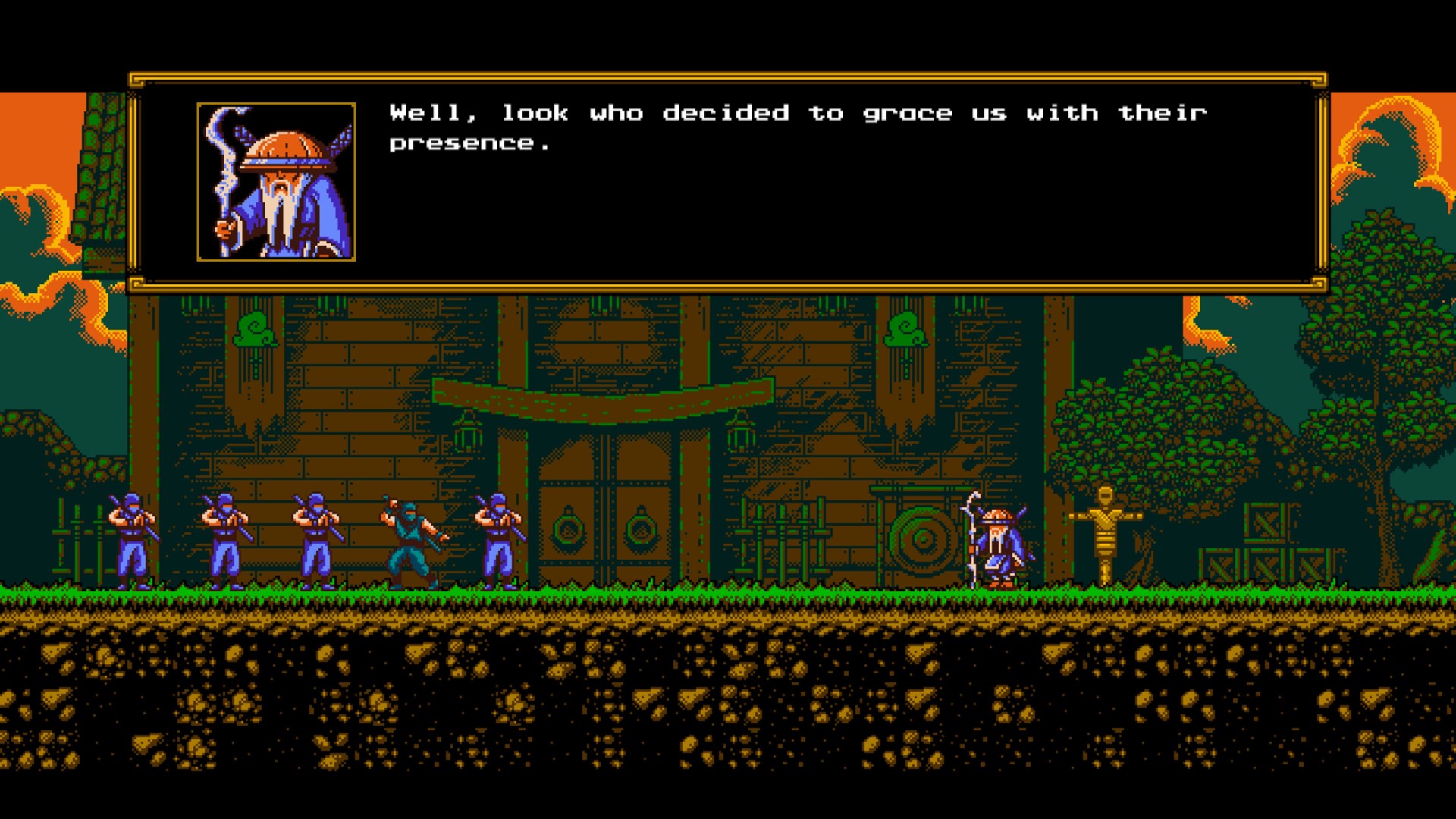

So through this competition, Canada started inventing games that are unfundable anywhere else. Because of that, we have these weird unique games that are sometimes very successful. Like an 8-bit game called Messenger from the Sabotage studio from Quebec city, published by Devolver.

Messenger (2018). Developed by Sabotage

For games like this, CMF covers 75% of the development costs. And they can pay up to 1.5 million Canadian dollars (about $1.2 million). Well, you still have to provide another 25%, but that’s a good deal, right?

What’s interesting is that if the product fails, you don’t owe anything. You are not risking personal finances, not even the company’s. The debt is attached to the product. So you can really take creative risks.

With so many incentives for devs already in place, I wonder if you’ve seen a spike in VC activities recently? Are people coming in now that have been previously focused on investing in other industries?

I’ve been involved in the industry for over 25 years, and I would say for the first 20, there were no VCs on the scene.

Now, many developers have made money. Like Epic, for example. They make piles of money with Fortnite, and they can afford to have their own in-house fund called Epic MegaGrants.

Other people have sold their gaming businesses and became multi-millionaires. And because they know the industry, they started mini VC funds for other devs.

There’s also the Embracer Group. They know the industry, and they have the money to invest in it.

So, over the last five years, an increasing number of those have started appearing. People with experience that know the industry from the inside.

On the other hand, there are also new people that don’t know the industry but they know there’s money to be made here. With the pandemic, the hype around video games has increased significantly. People started playing more video games. So our stats are going up. More people were watching the League of Legends event than the Super Bowl. That’s the language finance people in New York or on Bay Street [centre of Toronto’s Financial District — Ed.] understand.

Why people were afraid at first is because we were perceived for a long time as the movie industry where there’s one mega hit versus 25 movies that don’t make money. That perception has changed.

Unfortunately, something has changed about us as well. Big studios became so advanced in data mining, trends scouting, etc. It’s almost becoming scientific and you don’t want it to become too much like this because it makes people go the safe way. That takes away from imagination. There’s a game called Spiritfarer that Le Monde called the most beautiful game of the year. That game makes you think philosophically about death. Do you think anybody in a survey would say they want a game that would make them think about death? I doubt that! And yet, the game is out there, it’s beautiful and it’s a total success.

Spiritfarer (2020). Developed by Thunder Lotus Games

So yes, there are tools now to reassure investors, but you still have to go in fields that haven’t been corrupt yet.

So, in Canada, there’s plenty of flexibility in terms of where to get funding from. I wonder what it means for the country’s publishing market?

The role of the publishers has definitely evolved. You used to need somebody who knew the buyers at Walmart, someone to pay for the boxes and the CDs. With the dematerialization of games, that cost has disappeared. Self-published games can be very successful.

The Messenger creator Sabotage is soon launching a new game called The Sea of Stars. They raised $1.6 million on Kickstarter. They have a community, they have money, so they can be self-financed.

The Sea of Stars (2022). Developed by Sabotage

However, not everybody has that chance. So publishers can still help you with funding. Sometimes games struggle to stay within budgets. There’re always bugs. There’s feature creeping. Unforeseen things will happen. This might make you need external help. And even though you had thought $2 million would be enough, you’ll need extra $200K. And the publisher becomes a savior. Plus, publishers still know the market, they have contacts in the media so they can help with exposure.

Over time, as it’s becoming increasingly feasible to self-publish, publishers will probably have to lower the percentage they ask for. It’s already happening. Sometimes I negotiate deals [on behalf of my clients among indies] and I get better deals than the initial offer. Obviously, the game has to be promising.

And this is something that’s happening across the globe. I wonder, though, for all these good things that the Canadian gamedev scene enjoys, there must be challenges specific to the country?

First of all, just like anywhere else, you still need to get a lot of money.

Second, looking for qualified manpower is a challenge. There are so many studios in the country, with many that came from abroad, there’s a competition for resources. The salaries are getting higher and higher. Right now, it’s difficult to find mid-level employees. So manpower is an issue.

Remote work is another one. But this is changing, too. There are companies where they have two coders in Kiev and one graphic artist in Paris and a game designer in Montreal – and they make very good products.

Discoverability is a problem, again, like everywhere else. That’s where publishers come in because they can help you improve discoverability. We don’t have enough local publishers but a few good initiatives are underway.

With CMF actively supporting experimentation, it is theoretically easier for devs to stand out from the crowd. Although that will still be hugely different depending on whether you are a big studio or an indie. Speaking of which. You’ve been with Ubisoft and you’ve also been with Frima, so you would know first-hand how the Canadian gamedev scene is balanced between big AAA companies and indie studios.

For a while, there were many big studios and only a few small indies. And this was great for the time because big studios created the culture of making games. When I was with Ubisoft, we had training. We were trained, for example, not to cover it up if you have a bug. Because you might think you can figure it out, and then you don’t, and you miss the milestone. We were trained to keep feature creeping at bay and not suddenly decide it should be a cat when the dog animation is already finished. We were trained not to neglect pre-production.

So we learned from the big ones. It took time. Warner has been there for 10 years, Ubisoft for 20. But now what has started to happen is that a lot of senior developers from Warner or EA meet at an IGDA cocktail, become friends and decide to make their own game! And then you have an Eidos coder with a Ubisoft animator, and they create a start-up. Increasingly, that’s what’s happening in Canada. Senior or mid-level devs join forces to make a game and they go to CMF. And they are so professional and experienced!

So the balance is slowly shifting towards indies because these experienced developers decide to do their own thing.

Big studios are great because they create lots of jobs and provide a culture of game development. But not everybody likes big structures. And there is crunch. So some devs can decide they simply want to make a very creative game that will not necessarily keep getting sequels until the series has been chewed as a gum that doesn’t taste anything anymore.

Indies are on the rise. And that’s absolutely something to celebrate! To wrap it up, how would you describe the specifically Canadian brand of video game development?

Americans say that Canadians are boring, too nice. I met a guy in Los Angeles. He told me this joke. Imagine there’s a huge party in Canada, and everybody’s drunk in the pool. How do you get the Canadians out of the pool? You say, “Get out of the pool please.”

First of all, believe me, we can throw a good party. Second of all, the perception is that we’re too nice. And there is a lot of truth to that. In our culture, we have a lot of respect for the difference of opinion. That’s one of our social values.

They even call our healthcare system socialist because medical care is free. Education is very accessible. We have a vision of a country that will take care of you.

And that makes our games different. We don’t need these violent games where you shoot your way to victory, with bombs exploding around you.

There are a lot of games from Canada that are more collaborative, prompting players to achieve goals together, not against each other. This is, I would say, a flavor to our game development culture, society’s imprint. So even though we’re the crazy ones creatively, we still share those values.

Crazy but polite! But do you think too much politeness might stand in the way of productivity? Like if you want to offer some justified criticism, do you have to first wrap it in a lot of layers of niceties just to reduce the potential trauma of upsetting somebody?

I haven’t thought about it like this because it’s so natural for me. I was a CEO, a vice-president, a producer, but when talking to subordinates, I approached them as colleagues, as equals, even though I had the power of the last word. I’m not hierarchical that way.

Does it negatively affect productivity? Maybe sometimes. But sometimes, it will increase productivity because if you feel respected in your creativity, in your initiatives, you might be more motivated because you will be much happier.

So true. This is definitely something that studios in other countries could learn from Canada. Thank you for the interview!