This article by Josh Bycer originally appeared on game-wisdom.com on Jan 19

I’ve begun writing my fourth book on horror design which has meant spending a lot of time with horror games old and new. Revisiting Silent Hill 4: The Room has given me a greater appreciation for it and the series. For today, we’re going to talk about how modern horror (especially from the indie scene) forgets some of the big lessons from the classic franchise.

Josh Bycer

author of “20 Essential Games to Study” and “Game Design Deep Dive Platformers”

owner of game-wisdom.com

Pacing

I have written extensively about pacing when it comes to horror, and it will be a major part of my design book. When it comes to horror games today, they tend to mess up when it comes to properly pacing out their terror. Either the horror is too slow — leading to the player becoming bored and lowering the tension — or it’s too fast, with the player constantly having to deal with the terror and stay in a constant state of tension.

Part of this problem has been the overreliance of jump scares and basic event triggers used by horror designers. At this point, I’ve come to expect a jump scare happening at any time in any horror game. So, it was to my surprise while playing Silent Hill 4 that I didn’t run into a jump scare for almost the entire play.

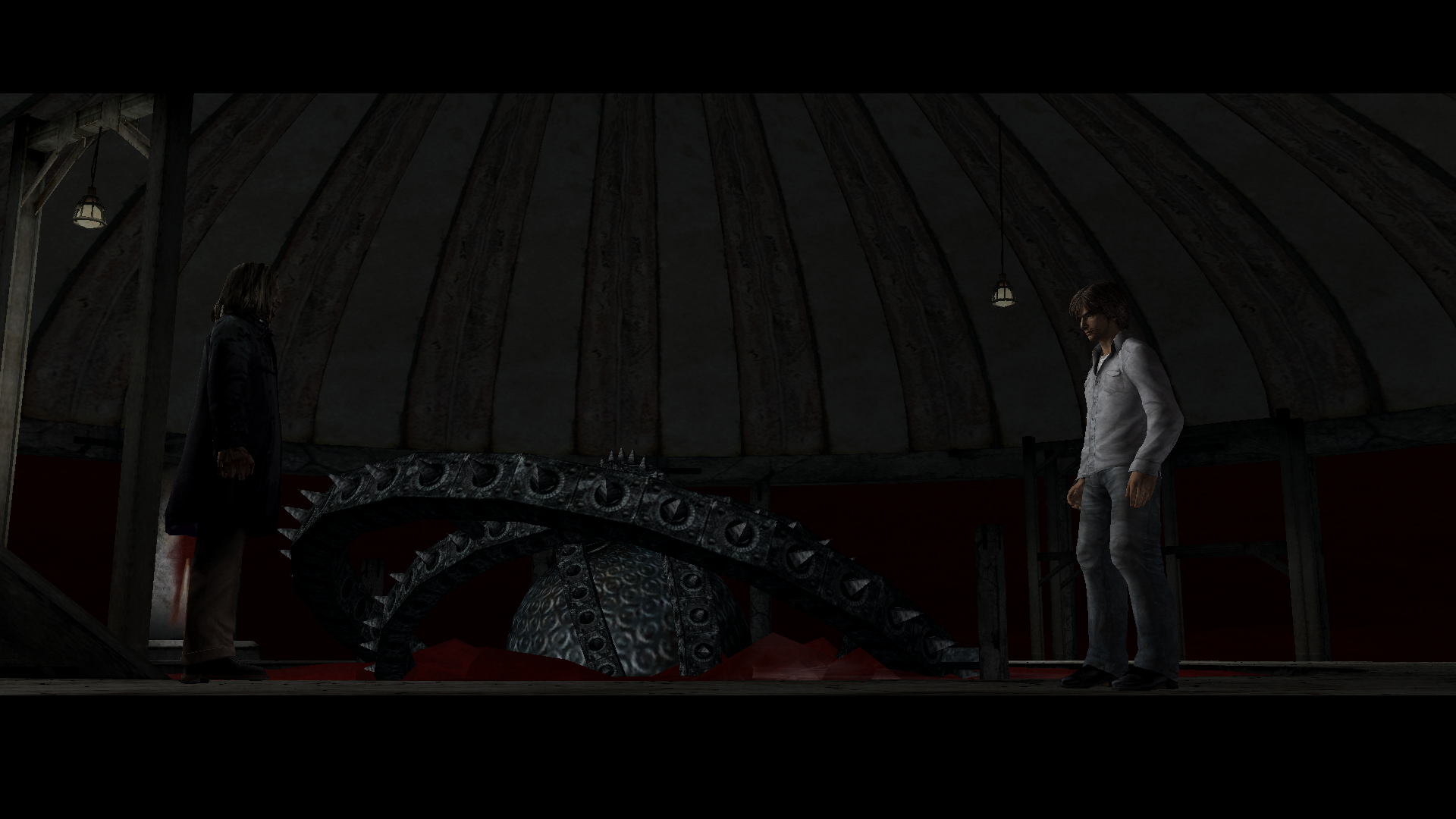

The game doesn’t stop to introduce a new monster via a cutscene, one second you’re moving through a prison, the next there’s a giant monster with a baby doll’s head coming at you. The game leaves the player alone just enough for the setting to start to get into their heads. Part of this is trying to figure out what’s going on and takes me to a major failing of indie developers that many view as a positive.

Lore vs. Plot

I may do a full post on this topic, but it certainly fits here. When it comes to storytelling, there is a difference between the lore and the plot and what they mean for the narrative. Lore is the story of the world and plot is the story of the character (AKA protagonist).

One of the major turning points for videogame narratives came with Demon’s Souls and soulslike design: by focusing on the lore as opposed to the plot. The point of the series is that you are not the hero destined to save the world, all the major players and events have long since happened. There is a wealth of history in each of the games, and many people have spent hundreds of hours to try and make sense of it all.

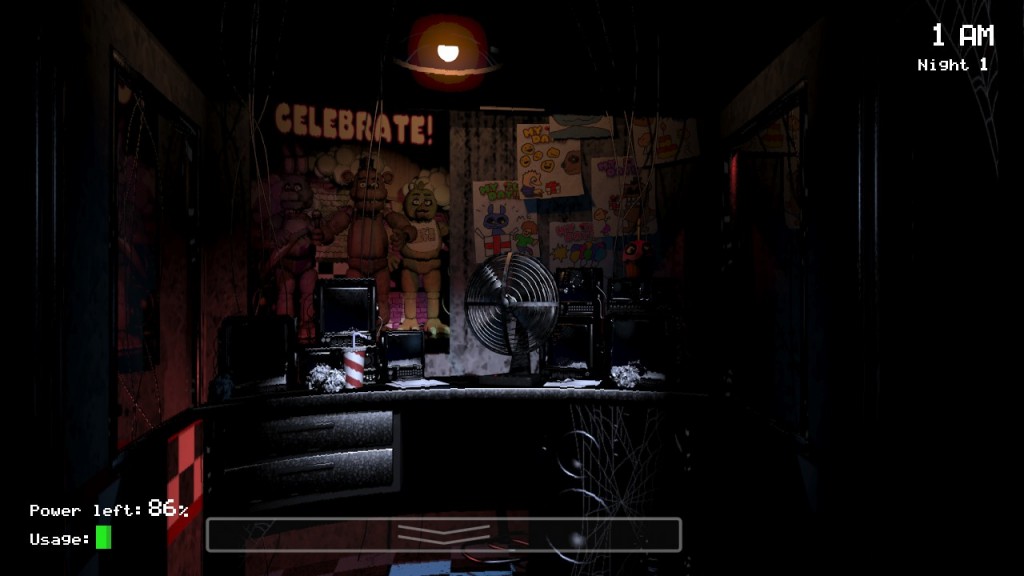

What this means is that you/your character means nothing to the plot: You have no dialogue, no interaction other than to kill, and no real stake in the story of the games. This kind of focus on lore really blew up with the rise of indie horror—Especially the Five Night’s at Freddy’s series. The reason why lore worked so well is that the developer can go in-depth about it without needing to put it directly into the game or mechanics. Lore can also be transferred to future games in the series and gives fans a sense of discovery as they try to put it all together.

The problem, in my opinion, is that this is the opposite of what makes a good horror story. There’s no real mystery to explore, nothing is really happening in the now that the player can experience or learn about. Everything that had meaning has already happened and you don’t really matter to the story itself. Even if the game has an actual character, they are often just the vessel for the player to inhabit.

Good storytelling makes us care about the character as well as the world

This is where plot comes in, and why the Silent Hill games still work for horror. Each game has lore in the form of Silent Hill and the events surrounding the town, but it also has plot with the main character.

We relate to characters like Harry Mason or James Sunderland because they have a reason to be there and that is part of the mystery. Silent Hill 3 being a direct sequel to 2 in terms of the story has even more weight to the story dealing with the events of Heather Mason and her connection to everything.

With Silent Hill 4, Henry is just as clueless about what’s going on as the player, but he isn’t a voiceless protagonist. The player is quickly introduced to the situation, the rules of what’s happening, and then it’s off to figure out why everything is happening to Henry. Speaking of “voiceless”, there’s something else I need to talk about in terms of modern-day horror.

The People

Horror games are undoubtedly about isolation, but there is such a thing as too much isolation. One of the most effective cost-cutting techniques we’ve seen from indie developers is using audio logs and text dumps as a replacement for characters (and having to animate/render them). However, this goes back to the first section talking about the issue of pacing and tension. When there is no one else in the area and nothing going on, it hurts the tension that the game is trying to pull off.

Character interaction is an important part of storytelling as it is our chance for the protagonist to share their thoughts and impact what’s going on. This next sentence is going to be shots fired on just about every indie horror developer, but it needs to be said: I am sick and tired of having, or listening to, one-way conversations with disembodied voices. When the protagonist is not affecting (or responding) to the story, it makes it hard for us to care about them or root for them to succeed. Unless you are making a game where the player is literally the character, the protagonist needs to interact with the people in the game.

The hands-off storytelling nature of modern horror games removes a lot of the tension and character growth

With both Bendy and the Ink Machine and Amnesia Rebirth, our only signs that our characters have any emotion or interest in the plot are a few sentences of dialogue in the beginning, and random mutterings to themselves to do something. Bendy is very guilty of this, with the game constantly referencing the main character as being important or connected to the events and having no lines of dialogue letting us know how they feel about what’s happening. There is only one part in the entire game where the main character has a conversation and it gives us nothing about who this person is.

Part of the mystery of the Silent Hill games is interacting with the people you meet and figuring out their relationship to the events. Even though these scenes don’t occur frequently, they give us a chance to ease off the tension, provide information to the player, and most importantly: Give the main character some time to interact with the story.

Scary Puzzles

Puzzle design is a topic in of itself (and something I covered in an earlier piece), but it’s another area where modern-day horror games have fallen behind. Many horror titles have no puzzles whatsoever or combat—meaning that there is no actual interaction with the world and the player is essentially just watching a movie. Other times, puzzles feel completely out of place or not in the universe of the game. A puzzle is not about just finding a key in the environment, but figuring out a solution, and it’s where a lot of horror fails on.

Horror must be very careful with puzzle design. A puzzle needs to be complicated enough to make the player think about it, but not so demanding that it takes the place of the actual horror. I’ve quit many horror games when I got stuck on an annoying puzzle or section and any tension built up was lost. Puzzles need to make sense for the situation and environment that they’re in. Silent Hill 2 had an interesting solution for this: Have both a combat and puzzle difficulty slider. The puzzle difficulty slider affected the kinds of clues given as well as the overall puzzle complexity.

Silent Hill 4’s puzzles aren’t the best in the series, but they each fit their respective universes. Each area has a kind of one “macro puzzle” that must be solved to unlock the next area. What makes it all work is that each puzzle feels like it makes sense for the area, and they’re not repeated from world to world. You want to avoid having puzzles for the sake of having them, and please — no more Towers of Hanoi puzzles.

The Give and Take of Combat

For the final lesson, let’s talk about combat. As with survival horror games for the time, the Silent Hill series does have combat in it. Truthfully, it is on the janky side and certainly not the best. This comes from a time when to make characters feel weak or add tension, character controls were left to be very clumsy. But clumsy combat is still a better take than no combat, and in a weird way, does help the horror of the situation.

Your combat options in Silent Hill: The Room are limited to melee weapons and a few guns that require ammo. Close ranged combat is very finicky, can be hard to hit the enemy, and doesn’t do much damage unless you charge up. Ranged damage is always preferred, but you are limited by the number of bullets you have (and inventory space to hold them). This creates a dynamic where the best option is to run away and only fight when you absolutely must, or to clear a space to search. I won’t spend as much time on this section, as it’s a topic I’ve talked about many times before, but the point is that fight, or flight is an essential part of horror and removing one of the choices hurts the tension in my opinion.

There are more creative ways of having combat while still not making it always the best option. You could make weapons have durability, certain enemies that can’t be fought easily and I’m sure other ways. Titles like Alien Isolation and the recent Resident Evil remakes introduced alpha antagonist enemies that would hunt the player down and couldn’t be killed, while still allowing them to fight normal enemies. There is the option of allowing the player to better make use of their environment to trap or disable enemies, such as in Clock Tower and Haunting Ground.

Removing combat and replacing it with nothing robs a horror title of its tension

With Silent Hill 4 this comes in the form of the specters that begin to stalk the player. They can be attacked and temporarily knocked down, but the only way to completely stop them is to use one of five special swords that are found throughout the world.

Room Rummaging:

Overall, Silent Hill 4: The Room is not as good as the original trilogy. The back-half became a padded-out slog coupled with an escort quest. The game forgot one of the core tenets of the original three games: Focus on the storytelling and adventure, not on the combat. Too many areas were just filled with enemies, which was funny because the best strategy was to just run around everything.

Still, it is retroactively better now compared to some of the other horror games I’ve played. Horror isn’t always about loud music and jump scares, but the slow burn of knowing something is wrong and just waiting for the creepy shoe to drop.

***

Josh is currently working on his fourth book Game Design Deep Dive: Horror with book 3 due out later this year on roguelike design.