The Shattering is a first-person story-driven psychological thriller with horror elements. It came out on April 21 and is currently available on PC.

Rather than relying on the genre’s clichés such as jumpscares and the generous use of darkness, The Shattering invokes fear through the absence of information. It defines the overall design of the game, with its shifting environments, invisible characters and the color palette that is dominated by various shades of white.

The Shattering is the latest title from the German publisher Deck 13 and the first title for the development studio called Super Sexy Software. Its members are based in Poland, France and Switzerland.

We sat down with Marta Szymańska, Founder at Super Sexy Software and Game Director on The Shattering, to discuss the studio’s debut title.

Marta Szymańska, Founder at Super Sexy Software

Oleg Nesterenko, managing editor at GWO: Many reviewers on Steam identify the game as a walking simulator. Would you agree with this definition?

The game doesn’t have any complicated mechanics, there are no puzzles or failure conditions. So I think there is nothing wrong with calling The Shattering a walking simulator.

When we were working on the game, we didn’t establish a certain game style we would follow. We didn’t say that we want a walking simulator. We just focused on the story and how we can tell this story. How we can show it.

The idea for The Shattering came from the study you made into the contrast of white and black in horror and culture. Could you tell us about your research?

It started with my thesis that investigated the differences between the Western and Eastern understanding of the color white. In Western countries, white is traditionally connected with purity, innocence, peace, virginity, safety, heaven, faith and spirituality. In Eastern countries, white is the color of death, emptiness, isolation.

We went with the Eastern understanding of the color white, but we wanted people to perceive it the same way they perceive the color black in popular horror movies, although in a more psychological and therapeutic way. Since white also symbolizes purification of thoughts or actions (the white void), it perfectly matched our idea of how we want to show our story in the game.

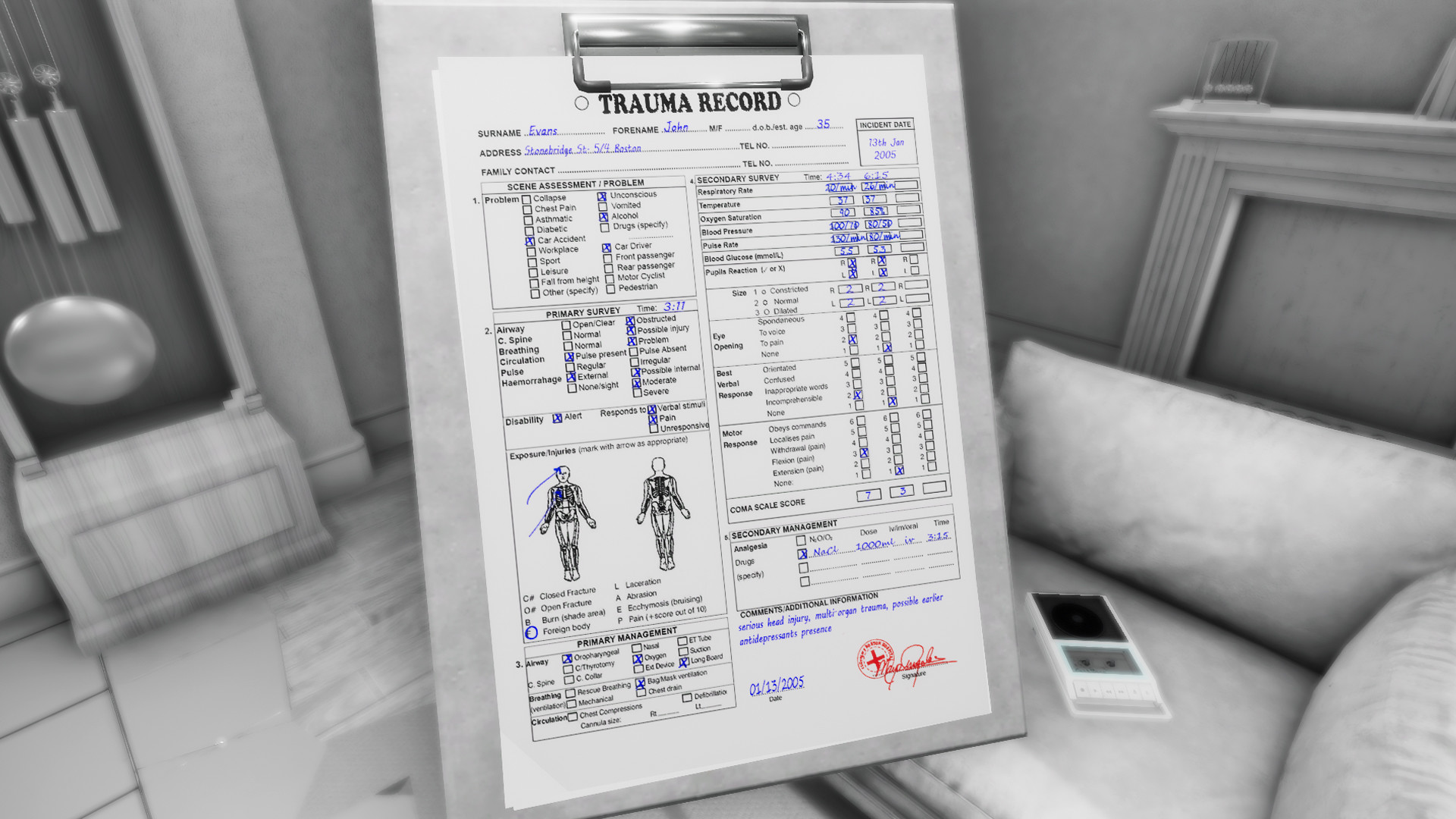

Additionally, when we were already planning The Shattering, we learned that some people dream in black and white. In those people’s dreams, color only shows up as a symbol or a highlight of something important. We used that idea. Things that are important have color in our game. For example, blue draws arrention to certain objects and signifies a particular mental state.

Another interesting aspect in my initial research was focused around the notions of horror vacui and amor vacui, which in Latin mean “fear of emptiness” and “love for emptiness.” We shatter things in The Shattering, revealing nothing but empty white space. Interestingly, for some people, the lack of detail or the absence of familiar objects can be a source of fear.

Less is more here. Rich environments (like the lobby in Act 1) are gradually replaced with empty spaces (like in Act 3). This reflects the journey of the protagonist and the player, as their view of the world begins to shatter and they go on to embrace the void at the end of Act 2.

Fear of emptiness… Is this why there are no visual representations of the characters in the game?

Again, it’s just like in dreams sometimes. We feel that people are there, even if we don’t recognize their faces.

We also didn’t want to show faces or give up any physical details about our characters so that players can complete them in their minds.

This level of abstraction can be difficult to pull off in a video game. Were you concerned this might drive players away from your game?

It was challenging to make some things abstract but still understandable for players. Thanks to a lot of playtesting and feedback from our QA group, we made sure that everything was clear and that players knew what to do. As for the general meaning of John’s story, we deliberatly left space for interpretation, even though all the clues are in the game. One of the most exciting things we observed was that each player had a different understanding of what happened, and none of them were wrong!

Based on the feedback, did you find that The Shattering is effective as a horor game?

I am a huge fan of the horror genre, and when I was beginning to approach this project, I wanted to make a horror game that had never been seen before. I wanted it to resonate with inner feelings rather than rely on external events (eg. jumpscares). However, all of us have a different understanding of what scares us, so we stopped thinking about this project as a horror game. We focused on how we can cause ceraint feelings in the player. How we can make them sad or uneasy about the direction the story is taking. All without things jumping out of closets.

That’s why the absence, the minimalism, the void spaces worked here so well. We got a lot of positive feedback from people who were saying “I don’t like jumpscares, I don’t like horror in general, but this game makes me afraid on a different level, without making me too scared to continue playing it.”

The Shattering represents a different subset of the horror genre that I sometimes like to call “white horror.” You know, given the game’s aesthetic.

The Shattering explores the workings of the protagonist’s disturbed mind. Was this theme relevant to you?

We wanted to create a new subgenre of horror. So we experimented with color. We also experimented with the way we are telling the story. John’s mental state served us as a tool to tell a story of a shattered mind. The mind that is confused and needs help to understand what happened. I think this subject is also something I am personally interested in.

In your dev blogs, you said you consulted mental health professionals to add authenticity to your game. What did you learn from them that you used in the game?

We had two close friends that we had sessions with at the beginning of the project. They helped us to create the protagonist’s personality. These sessions were one of the most enlightening moments in creating the game. From them we took the general story of John, created his trauma, and thought about how he can react to certain questions or actions. The sessions also helped create the character of the doctor. We learned how questions are asked, what the tone of the doctor’s voice is. And we learned a lot about the treatment process. All that can be seen in the game.

The Shattering was first conceived in 2014 and has gone through numerous iterations since then. Could you walk us through how the game has changed over these years?

The first idea started back when we were still studying. We had to take some time to learn how certain things are done, what we can achieve.

The first iterations of The Shattering resembled traditional horror games.

Back then, we had much more open environments, we were generally planning much more than we could handle at the time. When we realized how much time and effort the project would cost us, we decided to take smallers steps (after all, we are a 5 person team). We turned towards the indoor scenes, and worked harder on the shattering effect we used on objects and locations. We focused on just one apartment (in Act 4). After that, we felt more confident to expand our locations and the Acts themselves. I remember how we gave our first beta to the playtesters, and the level of abstraction was a bit confusing. So we worked on parts that felt weaker, and after another round of playtesting, we finally got the feedback we wanted.

You obviously paid extra attention to how the game sounds. Could you tell us about your work on the music and the sound design?

Our music is made by Tim Dorr, he is a French musician and composer. When we started working with Tim, he wasn’t familiar with Unity, and we needed to introduce him to this new world. I think the strongest point in creating the music for the game was the freedom, the power of the unknown. Since we all were learning, there was never a point where we stopped experimenting and trying new mechanics. Tim always asked me about what feelings I wanted in what moment, and then he tried to express them through music. We had our share of abstractness in the game, but working on the music was by far the most abstract thing we had to do!

How did you sign with Deck 13? They are typically focused on skill-based games with more action and adventure elements.

I think we met with Deck13 in 2016, in Warsaw on some game showcase. We pitched them the idea of the game, and I think the chemistry was just there. They liked the idea, but also I think they liked the whole team. We weren’t very business-savvy about making games, but the passion was there.

According to your website, your goal at Super Sexy Software is a revolution in the way our society thinks about games. What does that entail?

Since we started the project, we’ve always been thinking big. We want to educate people about games, especially those people who think it’s just a waste of time. In our opinion, games are a form of artistic experience that beats movies and books in terms of the recepient’s agency, its interactivity.

That’s why we didn’t want to make The Shattering difficult, we wanted more people to be able to play it and to see how immersive games can be.

Marta, thank you very much for your time and good luck with the revolution!

***

Dont’ forget to check out the extended video version of the interview with Marta: